Book reviews: Empire of Cotton | Wallflower

Empire Of Cotton: A New History Of Global Capitalism

Sven Beckert

Allen Lane, £30

THE history of an era often seems defined by a particular commodity. The 18th century certainly belonged to sugar and the 20th to oil, but the 19th belonged to cotton; and as Harvard historian Sven Beckert incisively demonstrates, this brought misery to millions of slaves, sharecroppers and millworkers.

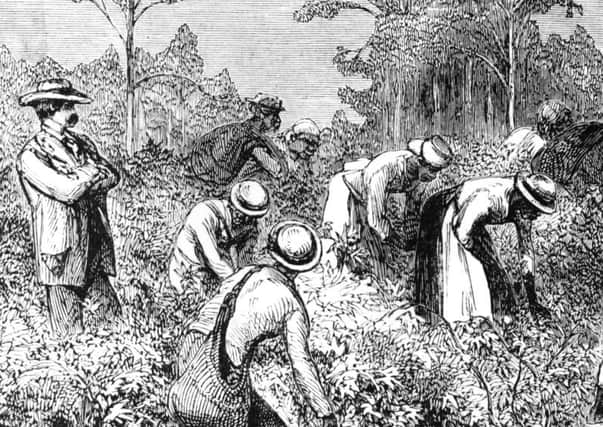

“Until the 19th century,” Beckert explains, “the overwhelming bulk of raw cotton was spun and woven within a few miles from where it was grown.” Nothing changed that more dramatically than the slave plantations that spread across the American South. These showed that cotton could be lucratively cultivated in bulk for consumers as far afield as another continent, and that realisation turned the world upside down. Without slavery, he says, there would have been no Industrial Revolution.

Advertisement

Hide AdEvery stage of the industrialisation of cotton rested on violence. As soon as the profit potential of those Southern cotton fields became clear in the late 1780s, the transport of slaves across the Atlantic rapidly increased. Cotton cloth itself had become the most important merchandise European traders used to buy slaves in Africa. Then planters discovered that climate and rainfall made the Deep South better cotton territory than the border states. Nearly a million American slaves were forcibly moved to Georgia, Mississippi and elsewhere, shattering many families in the process.

The search for more good cotton-growing soil in areas that today are such states as Texas, Arkansas, Kansas and Oklahoma was a powerful incentive to force Native Americans off their traditional lands and on to reservations, another form of violence by the “military-cotton complex”. By 1850, two-thirds of American cotton was grown on land that had been taken over by the United States since the beginning of the century. And who structured the bond deal for the Louisiana Purchase, which made so much of that possible? Britain’s Thomas Baring, one of the world’s leading cotton merchants.

It was not just in the US that planters’ thirst to sow large tracts with cotton pushed indigenous peoples and self-sufficient farmers off their land; colonial armies did the same thing in India, West Africa and elsewhere. And it was not only white Southerners who were responsible for the harsh regime of slave-grown cotton: merchants and bankers in the north states and in Britain lent them money and were investors as well.

Beyond violence, another major theme of Empire Of Cotton is that, contrary to the myth of untrammelled free enterprise, this expanding industry was fuelled at every stage by government intervention. From Denmark to Mexico to Russia, states lent large sums to early clothing manufacturers. Whether it was canals and railways in Europe or levees on the Mississippi, governments jumped in to build or finance the infrastructure that big cotton growers and mills demanded. Britain forced Egypt and other territories to lower or eliminate their import duties on British cotton.

Beckert has a larger ambition, however, than just telling the story of cotton; he wants to use that commodity as a lens on the development of the modern world itself. This he divides into two overlapping phases: “war capitalism” when slavery and colonial conquest prepared the ground for the cotton industry, and “industrial capitalism” for the period when states intervened to protect and help the business in other ways. This makes Empire Of Cotton read a bit like two books, with one of them incomplete. Cotton’s story Beckert more than fully tells, but his analysis of capitalism really requires a bigger-picture scrutiny of other industries as well.

About the history of cotton itself, Beckert is on firmer ground. Today, a “giant race to the bottom” by an industry always looking for cheaper labour has shifted most cotton growing and the work of turning it into clothing back to Asia, the continent where it was first widely used several centuries ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAnd violence in different forms is still all too present. In Uzbekistan, up to two million children under 15 are put to work harvesting cotton each year – just as the mills of St Petersburg, Manchester and Alsace once heavily depended on child labour from poorhouses and orphanages. In China, the Communist Party’s suppression of free trade unions keeps cotton workers’ wages down, just as British law in the early 1800s saw to it that men and women who abandoned their ill-paid jobs and ran away could be jailed for breach of contract.

And in Bangladesh, the more than 1,100 people killed in the notorious collapse of the Rana Plaza building in 2013 were mostly female clothing workers, whose employers were as careless about their safety as those who enforced 14- or 16-hour workdays in German and Spanish weaving mills a century before.

Advertisement

Hide AdA long thread of tragedy is woven through the story of the puffy white substance that clothes us all.

Runaway

Peter May

Quercus, £18.99

GLASGOW 1965, and five teenage Glaswegians in a band called The Shuffle decide to forget school and everyday life and head for the bright lights of a bigger city. London, at once swinging and decidedly dodgy, is everything they thought it would be. On their first day there, while they are waiting at an agent’s office on the Strand, someone very like John Lennon advises them to start writing their own material. Round the corner, on the Savoy Steps, someone very like Bob Dylan is filming the trailer about Don’t Look Back – you know, the one where he stares at the camera, sullenly discarding large white cards with some of the lyrics of Subterranean Homesick Blues on them.

Just in case you haven’t got the idea that the wannabe famous five have accidentally found themselves at the world epicentre of cool, a society doctor invites them to stay at his Chelsea mansion (Bridget Riley paintings on the walls, naturally), where there’s an LSD party, a death and a murder.

Fifty years on, someone else who was at that party is murdered, and the Glaswegians head for London again because one of them knows who did it.

They’re all pensioners now, either dying, or disappointed, or half lost to drink. Regrets? They’ve got a shedload. Looking back, The Shuffle’s Sixties starburst of optimism shines out more than anything any of them have achieved since, even despite the tragedy.

Peter May’s last standalone novel, Entry Island, was voted the Scottish Crime Book of the Year, and the publishers are hyping this up to the hilt, hailing him as “the UK’s best crime writer” and highlighting the million-plus sales of his preceding Lewis Trilogy.

Advertisement

Hide AdCertainly, I can see it working as a film: the pensioners’ progress south is a bit of a cross between a Last Of The Summer Wine caper and a state-of-the-nation road movie. There’s a love interest too, and a real emotional edge to those regrets. As a novel, though, it’s rather like The Shuffle’s first day in London: a bit too obvious.

David Robinson

Wallflowers: Stories

Eliza Robertson

Bloomsbury, £14.99

IN ELIZA Robertson’s captivating debut, people drown in grey water, shacks burn on stony beaches, planes crash into rivers, hummingbirds are trapped and tethered to wrists, neighbourhoods flood. Grief and loss cast long shadows over these stories, which sometimes bring us to the threshold of disaster and sometimes explore its aftermath.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn Who Will Water The Wallflowers? a girl cat-sits for a neighbour, sharing boiled eggs with a family of raccoons that live in the hedge, while her mother remains at home roaming their empty rooms and washing in their bath the river stones she collects for a massage studio. All the while there are ominous warnings about flooding.

The story ends at the precipice of loss: just as the mother places stones in her pockets to bring next door and show her daughter, a levee breaks. Muddy water, “a sinewy rush of it, the brown of upchucked peanuts,” uproots trees. Amid the catastrophe, there is a delicate beauty in the details Robertson selects, such as the flowers in the flooded bathroom suddenly thriving with all the water. “The wisteria sucks at it,” Robertson writes. “The peonies open their petals and sing.”

Robertson, a Canadian now living in Britain, says she is drawn to “a particular, slanted reality”. Often the grief in her stories is so huge the telling requires an oblique approach that can contain the crushing devastation without slipping into sentimentality. In Ship’s Log, the story unfolds as the young narrator digs a hole to China in the aftermath of his grandfather’s death. In Roadnotes, a woman writes travel letters home to her brother as she journeys south, following the wave of autumn colours from Vermont to Missouri, making discoveries about her dead mother and their dysfunctional family along the way. In the peculiarly titled Thoughts, Hints, And Anecdotes Concerning Points Of Taste And The Art Of Making One’s Self Agreeable: A Handbook For Ladies, abuse and revenge are revealed through an etiquette manual: “Learn to keep silence even if you know your husband to be wrong. The stoutest armour is a cordial spirit (and spirit in the glass doesn’t hurt).”

In the particularly powerful Where Have You Fallen, Have You Fallen? the action unfolds in reverse and interweaves mythology while telling the story of a girl who has lost her mother and brother in a boating accident and must now make a new life in a faraway town with her uncle.

Robertson pays careful attention to the smallest detail, the one rich with opportunity and heartbreak: “She was seated with her uncle in the front row, and could even detect a milk stain on the reverend’s chest. It felt so disrespectful, that stain.” But Wallflowers also asks big questions, not only how we survive loss and achieve intimacy, but whether we are strong enough, like the flowers in the flood, to stand straight and sing our sorrows to the world.

Natalie Serber