Book review: When the Clyde Ran Red, by Maggie Craig

In fact the new ILP Clydeside MPs were none of them more than pale red, and, if they went to change Westminster, Westminster changed them too. David Kirkwood would end in the House of Lords, as would Mannie Shinwell, raised in Glasgow but MP for a constituency in the north of England. The great idealistic orator James Maxton would become a favourite of the House of Commons; John McGovern would leave politics for Moral Re-Aarmament. Tom Johnston , Secretary of State for Scotland in Churchill’s cabinet would scurry around buying up copies of the book in which he attacked Scotland’s Noble Families – with members of whom he now found himself happily working.

Yet the reasons for anger, indignation and pity in the half century and more before the 1914-18 war were real enough. Glasgow, not in this alone among great 19th century cities, offered an unholy contrast of riches and privilege on one hand, hardship and exploitation on the other; “dirt, poverty and ugliness were all around”, noted Helen Jack (later Crawford) returning to Glasgow at the age of 16, and finding “Earth’s Nearest Suburb to Hell”; she would become a founder member of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Advertisement

Hide AdCraig has written a wide-ranging survey, and done so in an easy, accessible and generally engaging style. The best parts of the book deal with social, economic and cultural history, rather than politics. This is partly because in political passages she inclines, no doubt understandably, to uncritical partisanship. So, for instance, admiring the courage of the suffragettes whose “frustration boiled over into anger, direct action and much smashing of windows,” she pays less attention to the suffragists who believed that the violence actually damaged their cause and delayed their victory.

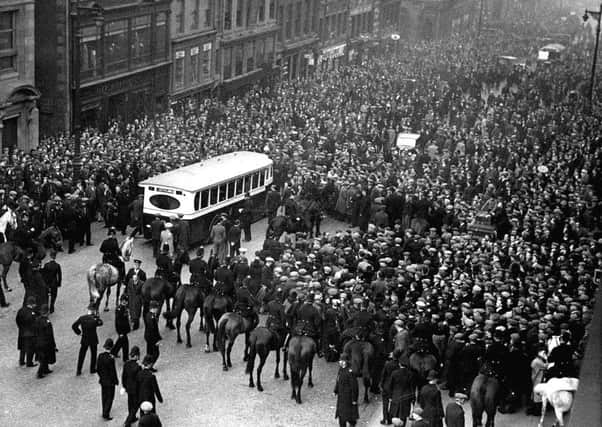

Likewise, while the response of the authorities to strikes and industrial unrest during the 1914-18 war was undoubtedly clumsy and harsh, many with husbands or sons serving in the Army undoubtedly regarded strikes which hampered the war effort with equal disapproval. The government may have overreacted, but it wasn’t unreasonable to fear that the example of revolution in Russia might be infectious. There was good reason to oppose the war – few now might consider it to have been anything but disastrous. Nevertheless at the time it had popular support. History written from one side, one point of view, is always unbalanced.

That said there is far more to praise and enjoy in this book, itself a revision of an earlier edition published in 2011. It is written with enthusiasm and sympathy, and most of the time generosity and fairness. It is in fact less a continuous narrative than a collection of related essays, taking us up to the Clydebank Blitz and sketchily treating later politics. It is always interesting, and if one may find it ultimately rather sad, even depressing, this is because it demonstrates that Scotland a hundred years ago was a much more serious and idealistic country than it is now, serious about improvement, serious in its religious faith. Serious in the belief that politics matters and that non-violent political engagement is a matter for reasoned argument, not slogans or catch-phrases. I don’t know that Craig set out to reprove the present by re-creating the past, but this is what she has done. Nevertheless, she bravely asserts that “one thing hasn’t changed, the democratic spirit of the Scottish people”. Really?

When the Clyde Ran Red, by Maggie Craig, Birlinn, 313pp, £9.99