Book review: Universal Man by Richard Davenport-Hines

Universal Man: The Seven Lives of John Maynard Keynes

By Richard Davenport-Hines

William Collins, 432pp, £18.99

John Maynard Keynes was one of the most remarkable Englishmen of the 20th century, but I suppose that many now are only vaguely aware of him as an economist sufficiently influential to have given his name to a theory of public economy, Keynesianism standing midway, as it were, between Marxism, which he despised, and laisez-faire (now known as “neo-liberal”), which he learned to distrust. But he touched life at many points and Richard Davenport-Hines’s engaging and sympathetic biography has seven chapters, each covering one aspect of his life, character and interests. They are: altruist, boy prodigy, official, public man, lover, connoisseur and envoy. The distinctions are fair, though there is inevitably some overlapping. There is already an outstanding three-volume biography by Robert Skidelsky. Davenport-Hines doesn’t compete with Skidelsky but complements him.

Keynes was an outstanding example of the public intellectual (though the private man is every bit as interesting). It is extremely difficult to write a biography for the general reader of a man much cleverer than oneself, and to do so admiringly yet critically, but Davenport-Hines brings it off. If Keynes’s life has one pre-eminent lesson, he writes, “it is that if confronted by conflicting alternatives, when choosing the way forward in practical matters, the sound principle is to take the more generous course” – a lesson one wishes politicians today would learn.

Advertisement

Hide AdKeynes became a great Establishment figure, but a self-made one. His family was middle-class, but he won a scholarship to Eton and another to the then predominantly Etonian King’s College, Cambridge. King’s would remain the centre of his life, and he was formed by its ethos of liberal humanism. He became a member of the influential Cambridge society of the Apostles and, like other Apostles such as Lytton Strachey, of liberal and sceptical Bloomsbury. Disciples of the philosopher GE Moore, they regarded friendship as a supreme good.

Briefly a civil servant before the First World War, he was recruited by the Treasury when war broke out, and had to deal with the unprecedented and unforeseen problems of financing not only Britain’s military efforts but those of our allies too. In 1919 he was a British delegate to the Versailles peace conference, where he was equally dismayed by the naivety of American idealism and the determination of the Allies to make Germany pay heavy reparations for war damage.

His book The Economic Consequences of the Peace combined compelling argument with vivid and amusing character sketches, some unfair. Many, such as the historian AJP Taylor, came to believe that the book did great damage by encouraging the Germans to believe they were the victims of a vindictive settlement.

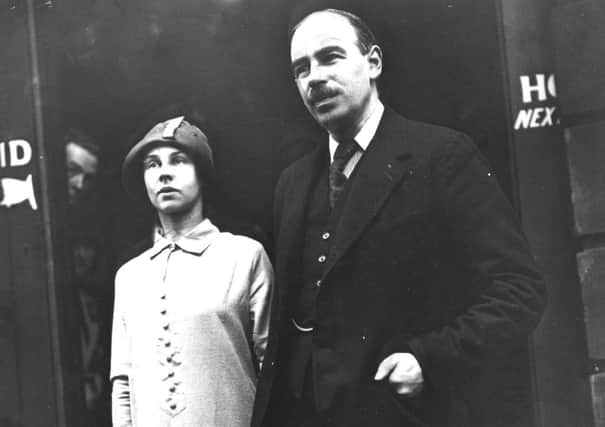

For the first 20 years of his adult life, Keynes, like other Bloomsburyites, was actively homosexual. Despite believing –correctly – that he was physically unattractive, he seems to have had no difficulty in finding partners. His emotional affairs were mostly with members of his own class and set, but he cruised the bars, Turkish baths and public places where pick-ups might be made. Homosexual practices were then illegal, and homosexuals lived in the shadow of the Oscar Wilde scandal. But Keynes was undeterred and the record he kept of his adventures is remarkably full. He appears to have escaped the attentions of the police and it is a mark of the decency of his casual and occasional lovers that he seems never to have been subjected to blackmail. In fact he evidently had a jolly sex-life, agreeably free of guilt or self-reproach. Then in his late thirties he fell in love with a Russian ballerina, Lydia Lopokova, and married her. Some of his Bloomsbury friends thought this a terrible mistake (though Virginia Woolf approved of Loppy). No matter; they seem to have lived happily ever after.

Keynes was inconsistent in his economics arguments, famously remarking that when the facts changed, he changed his opinion. His mind was quicksilver and he often found it impossible to hide his impatience with those who were slow to grasp his argument. Americans in particular were irritated by his air of effortless superiority and his recourse to sarcasm. From the mid-1930s he suffered heart problems, and consequent exhaustion, and his intense work in 1945-6 in helping to devise what was intended to be a stable world financial system contributed to his early death. Yet the Bretton Woods system endured for a quarter of a century, and nothing satisfactory has replaced it.

Among his many activities Keynes found time to create what became the Arts Council – he had always believed in public support for the arts, and this is one of his enduring legacies. Quirky, often difficult, his credo holds good today: “The political problem of mankind is to combine three things: economic efficiency, social justice, and individual liberty. The first needs criticism, precaution and technical knowledge; the second, an unselfish and enthusiastic spirit, which loves the ordinary man; the third, tolerance, breadth, appreciation of the excellencies of variety and independence.”

Advertisement

Hide AdSadly, we are no nearer to achieving this Keynesian balance than we were in his time.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS