Book review: Superman and Philosophy: What Would The Man Of Steel Do?

Superman and Philosophy: What Would The Man Of Steel Do? Edited by Mark D White

Wiley-Blackwell, 256pp, £11.99

They have ventured into comics before – Green Lantern & Philosophy: No Evil Shall Escape This Book; Iron Man & Philosophy: Facing The Stark Reality and Spiderman & Philosophy: The Web Of Enquiry – as well as piggy-backing on texts as diverse as South Park, Downton Abbey, Game of Thrones and, er, the music of Black Sabbath and Metallica. They are fun books, which every school ought to have in their libraries. Scotland has a proud philosophical tradition, though it is taught only intermittently on the curriculum. Any endeavour that redresses that is to be welcomed.

Advertisement

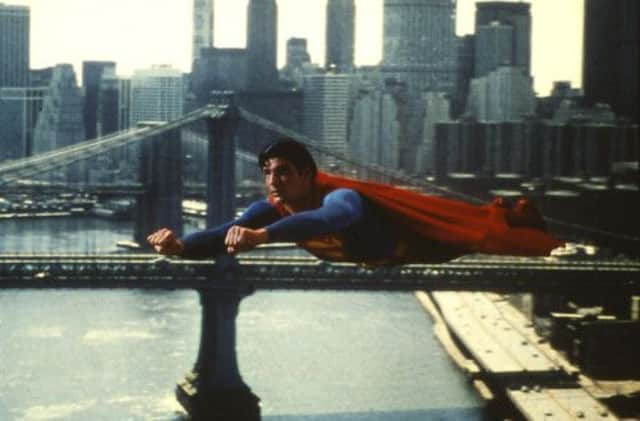

Hide AdThis particular volume arrives at an auspicious anniversary. For 75 years, readers have enjoyed the adventures of Kal-El, aka Clark Kent, aka Superman, ever since he first appeared in Action Comics #1, in April 1938. But – unlike Batman or the X-Men – he appeared as an intervention into a pre-existing philosophical discourse.

George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman had introduced the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, especially the Übermensch to English readers in 1903. Nietzsche’s ideas were, in the same period, travestied by Hitler. The best section of this book concerns how Superman relates to Nietzsche’s thought. It could be argued that Superman’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, deliberately and consciously sought to counter Nazified notions of the Superman: as several writers in the book observe, the character who most resembles Niezsche’s Übermensch – a figure who repudiates Judeao-Christian notions of morality in order to advance humanity – is Lex Luthor, not Superman. Indeed, Siegel and Shuster’s earliest engagement with the mythology was the 1933 story “The Reign of the Superman”, in which the “Superman” was a bald scientist bent on world domination. Superman is the incarnation of Judeao-Christian ideas: he defends the weak, feels pity, and – let us not forget – is sent by his Father to earth, where he is a better human than the humans, dies at the hands of Doomsday and is resurrected from the grave (or Kryptonian Regeneration Matrix). Perhaps “Superman and Theology” should be next.

Although at first Superman’s powers were somewhat limited (he couldn’t fly, but could jump really high; he didn’t have heat-vision or freeze-breath), the modern characterisation which offers him nigh-invulnerability came at a narrative price: how do you create tension if the character can do anything? The answer was moral dilemma, and several chapters here concentrate on moral philosophy. Should Superman save Lois Lane, or a bus full of children? Is the only way to deal, permanently, with General Zod capital punishment?

It is a pity that a number of the chapters rehearse the same summary of broad trends in moral philosophy; more than once the reader is told about utilitarianism (morality being a consequence of the maximisation of happiness and the minimisation of pain); deontology (actions are good or bad independent of consequences, with Kant’s categorical imperative as the key formulation) and virtue ethics (not the action but the actor).

Although the work of Judith Jarvis Thomson is mentioned, à propos of her investigation of secrecy, it’s peculiar that none of the writers invoke her development of Philippa Foot’s discussions of moral judgement and what might be termed ethical triage. Foot’s famous thought experiment involves that quintessential Superman problem – the runaway train – with the individual asked to push a switch to move the train onto one of two forks. Each fork is then weighted: one has a baby, the other a pensioner. One has a morally blameless individual, the other has two wife-beaters. How do we apportion value in such, admittedly very hypothetical, circumstances?

The moral questions extend to negative and positive moral obligation – do we have a duty to do things, or a duty not to do things – which at least attempts to unravel the paradox that Superman seems very good at dealing with Metallo, Parasite, Darkseid, Mr Mxyzptlk and Atomic Skull, but very bad at dealing with famine, AIDS, poverty, terrorism and Kim Jong Un.

Advertisement

Hide AdSuperman supposedly stands for “Truth, Justice and the American Way”, and the latter two require some elucidation. Much to the horror of Fox News, Superman renounced his American citizenship in Action Comics #900, although as several commentators here observe, “Superman” never had it in the first place. Andrew Terjesen deals with patriotism, though the piece could have benefited from an analysis of the more jingoistic versions of Superman in the 1940s (Action Comics #58 had the awful cover “Superman Says You Can Slap a Jap... With War Bonds and Stamps!”) Christopher Robichaud offers a very good piece contrasting the concept of justice in Rawls and Nozick, with a witty imagining of an ultra-libertarian Superman.

One of the frequent failings in many of the books in this series is that they reiterate famous philosophical ideas and substitute “Superman” or “Homer Simpson” or “Gregory House” for the more mundane version. By contrast – and especially interesting in our post-Levenson days – Jason Southworth and Ruth Tallman’s excellent piece on journalistic ethics deals with the “reality” of the Superman story. Clark Kent, we are reminded, manufactures stories, lies, fakes interviews and photographs, fails to disclose conflicts of interest, withholds sources, uses covert surveillance, and is as quick to defame perceived “criminals” as he is to cover up his own breaking into LexCorp and stealing information. If Superman derives his powers from the sun, Clark Kent would do well on the staff of the Sun.

Advertisement

Hide AdNevertheless, it is surprising how little of Superman is actually here. Posing the question “Do the residents of the Kryptonian city of Kandor know they are actually in a bottle on Braniac’s spaceship?” would be an easy way into Nick Bostrom’s trilemma on virtual worlds; and the plot in “52” about Luthor’s genetic creation of superheroes could lead to a discussion of the ethics of stem-cell research, the capitalist appropriation of scientific advances and trans-humanism generally. Hank Henshaw, the Cyborg Superman, would be a simple way to explore the philosophy of identity. Apart from the sections on Nietzsche, the only major engagement with continental philosophy comes in a superb essay by David Hatfield which uses the wonderful “Kingdom Come” story to explore the ideas of René Girard on violence and the sacred.

Classical philosophy was happy to use classical mythology as a means of exemplifying propositions – think of the Ship of Theseus in Plutarch; Achilles and the tortoise in Zeno; or the Choice of Hercules in Prodicus. This series – and this book – are bold attempts to revive that tradition, using the myths we have in our contemporary culture. Up, up and ontology!