Book review: The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins by Irvine Welsh

When Lucy Brennan proclaims her gospel, people listen. Fanatically zealous, she is a fitness trainer, 33 years old, a dangerous age to be peddling salvation, whatever the guise. She preaches muscle tone; she reviles the peddlers of junk food and its consumers, the “bloat bags” saddled with “reverberating flesh”. Lucy lives in the thick of Miami, near the beach; she won’t do drugs and is bisexual, taking her jollies wherever she finds them.

In The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins, Lucy’s contemptuousness of others – extending beyond her boyfriend, her gym instructor colleagues, and lard-bags, to the weak, the addicted, the victims of burger abuse and worse – is relentlessly conveyed in language plainly intended to skewer: “Part of me cheers when every gangbanger or lardass … ends up on a slab before their time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdLucy’s first-person, megaphone vitriol is a blast, at least to begin with. But, predictably, it wears thin. After 50 pages of witty put-downs, I reached for the ear-muffs, some crisps and a candy bar, a big one.

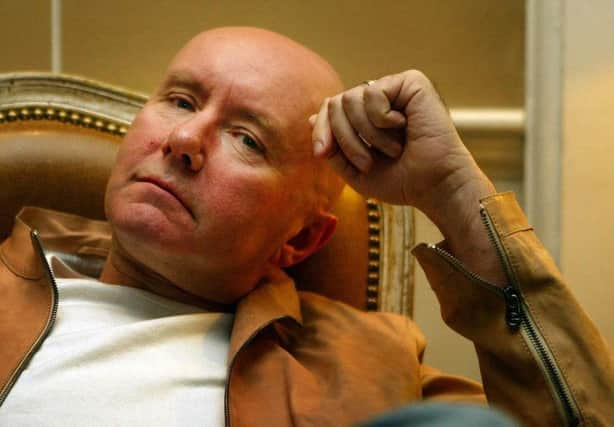

Irvine Welsh, though, was having a blast. Inside Lucy’s voice he was on a different kind of ecstasy from my chocolate hit. While I was already repelled, he was magnetically possessed by the power of her almost cartoonish persona. Attraction and repulsion are the Siamese twins of Welsh’s prose style. Lucy does both.

The “real” Siamese twins, Amy and Annabel, 15-year-olds from Arkansas, make appearances on TV screens in the corner during several scenes. They graphically symbolise interdependence – one of the novel’s signal themes. “One of them wants to go on a date, meaning that the other, the physically weaker one, will literally be dragged along.”

As Lucy sees it: “All America is enthralled by the so-called morality issue… Reading between the lines, one chick wants to f*** her boyfriend, the other is giving it the religious s**t. Those girls have divided the nation.” So, should the twins themselves be separated by surgery, thus freeing them? Where lies their happiness when intervention means risking their lives?

Television exposure, a different kind of intervention, has twisted those lives into crass entertainment for the masses, revealing another of Welsh’s themes: how social media threatens us all with the loss of privacy, dehumanising individual lives by, paradoxically, and cynically, deploying the tag “human interest”, turning its subjects into instant fodder for gossip. Pertinently, Lucy Brennan’s life, as we’ve known from the outset, is just such a case.

On a lonesome highway, at 3am, she disarmed a gunman, thus saving the lives of his two would-be victims. A passing witness – Lena Sorensen, who, as it happens, could be a poster girl for obesity – captures everything on her camera-phone, and, before you can say double-cheeseburger, has plastered Lucy’s heroics all over the media-sphere.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe din of instant celebrity sounds like the rattle of easy money. An über-excited, fixated PR woman tells our kickboxing new fangled media star that heroism –“an unusual quality these days” – brings its reward. A TV fitness show is mooted, with Lucy presenting.

Welsh must have been sorely tempted to take his narrative into the comedy-rich, satirical, easy-pickings of the media world, where Lucy would doubtless have flared like a passing comet. But Lena is not to be discarded. She is the irritant who will not leave Lucy alone, becoming the grit that makes of this novel a pearl-growing tale of human triumph against tricky odds.

Advertisement

Hide AdLena has depth as well as width. And she needs Lucy’s know-how to get her fit.

As Lena increasingly takes centre stage, the story prospers. Their symbiosis is taken to logical, if ludicrous extremes, with Lena chained up inside an apartment block, where Lucy force-feeds her with health food and fitness propaganda, encouraging Lena to record her thoughts on paper, a free association of ideas that leads us directly to Lena’s past.

She was once a starry, successful painter, who turned to sculpting – a serious talent, commanding big bucks, even while in art school, for her work. Welsh imposes upon her a later, much less convincing interest in taxidermy, thereby setting up the novel’s denouement, which packs a Roald Dahlesque punch, both darkly comic and ingenious. He allows her to acquaint us with her art school boyfriend Jerry, an envious leech who takes candid photos of her, and follows her, but is apprehended by Lucy. He subtly, convincingly brings his heroines together, their mutual need growing into love.

Love, dependency and sacrifice. Out there, the Siamese twins obey the same strictures, facing the cost of being together, the terrible price of separation. They make their decision. Lucy, too, has a price to pay – having dealt with Jerry, with Lena cleaning up the mess of his demise.

Lena’s memoir and Lucy’s hard-boiled first-person narration are interspersed with copious emails between the major and minor characters (Lucy and her business contacts, Lena’s mother and father), spoof critiques of Lena’s early exhibited work, a brief chapter from a crime book written by Lucy’s pain of a father, a former cop – by way of explaining Lucy’s pathology.

Welsh, whose ear for tasty dialogue has always been his forte, has never written with greater verve. Call it fast food, or a banquet of healthy cautionary wholegrain, this is a novel packed with energy.

Welsh’s fans will love its excess of sprinkled expletives, and its discipline, its ambition. Those new to his work will find perseverance has its reward.