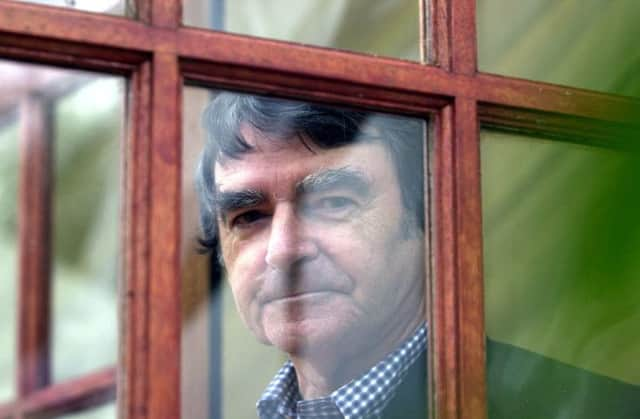

Book review: Quite A Good Time To be Born

Quite A Good Time To Be Born

by David Lodge

Harvill Secker, 496pp, £25

The title of David Lodge’s memoir of the first 40 years of his life, from 1935-75 is not ironic. 1935 really wasn’t a bad time to be born – if you were British. It was pretty awful if you were a continental European, and appalling if you were Jewish.

Lodge was old enough to be well aware of the war years, and have keen memories of them, but, though his home was in a south London suburb, he was never in any great danger. He endured the years of wartime and post-war austerity (in comparison with which today’s austerity is nothing), but he was one of the early beneficiaries of the 1944 Butler Education Act, which secured him a grammar school place. He went on to University College, London, fees and student grant paid by the state. He grew up in the early bright days of the NHS when its architect, the Labour minister of health, Aneurin Bevan, could confidently predict that, with improvements in the nation’s health, demands on the NHS would lessen. Best of all, he spent his youth in a country that was at ease with itself. We had defied Hitler, “stood alone” in 1940-41, and played a role in the liberation of Europe; we had a lot to be proud of.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe says he belonged to the lower-middle class. His father was a musician, playing in dance bands and jazz clubs, his mother, like most married women then, a housewife. An only child, he may not have been spoiled, but he was certainly coddled. He lived at home throughout his time at university, and says this was more common on the continent than in England. It was quite normal in Scotland too then, and, I rather think, in most of the English redbrick provincial universities.

CONNECT WITH THE SCOTSMAN

• Subscribe to our daily newsletter (requires registration) and get the latest news, sport and business headlines delivered to your inbox every morning

The family were Catholic, observing if not ostentatiously devout. That meant he belonged to a self-conscious minority. He was well-taught at Catholic schools where, he makes it clear, there was no evidence of sexual abuse. But sex would be a problem on account of the severity of the Church’s teaching on the iniquity of birth control. He met his future wife, Mary, on his first day at university. She was also Catholic, from a large family. He courted her for years, and, when they married both were virgins, and, like the young couple in Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach, ignorant about the sexual act. I’ve never found the ignorance of McEwan’s young marrieds convincing in a novel set in 1962, but in the middle 1950s Lodge’s inexperience was fairly common. No sex before marriage and no use of contraceptives in the marriage bed was certainly the rule for pious Catholics. The Lodges practised the rhythm method, unsuccessfully. They were soon parents.

David Lodge has pursued a double career, as an academic, university teacher of English literature, and as a novelist. This was even then less usual in England than in the United States, though both Kingsley Amis and John Wain were lecturers in English literature when they published their first novels. Lodge differs from them, however, in having been every bit as devoted to his academic career as his literary one, and more unusually still has been interested in theories of literature and written good, if (for me) decidedly difficult, books on that subject. Curiously, his novels, which have mostly been mainstream and realistic, might have been written by someone unversed in such abstruse matters.

He is a comic novelist, and a very good one, but there isn’t much comedy in this memoir, except when he offers some sharp pen-portraits of fellow academics. There was, for instance, Professor Alan Ross, well-known only for having sparked off the U/Non-U argument in the 1950s. He taught old English at Birmingham “but students complained that his classes were incomprehensible”. When he lectured so badly that nobody turned up to hear him, he was free to travel the world “visiting countries whose languages he claimed to speak, though no natives could ever understand him”. A bit like Anthony Burgess, I suppose, though I wonder what evidence Lodge has for the total incomprehension of the natives. Still Lodge’s memories and depictions of colleagues are generally so generous, even to the point of blandness, that occasional moments of academic cattiness are welcome. He was lucky to establish himself in university life when teaching was regarded as a don’s first duty, long before the pressure to engage in research on which university finances now depend.

Publishing was different then too: His first publisher was McGibbon & Kee. He doesn’t think they “had a publicity department as such, or, if they had I wasn‘t aware of it.” Editors decided which books to bring out, and there were no discussions with marketing men. “Publishing literary fiction was a simple business; your book was sent out into the world without your participation, and you sat back and waited for the reviews. But at least you could feel confident of getting some reviews, which cannot be said of most first novels today.” This was partly because fewer novels were published then, and partly because the standard practice was to review them in batches of four or five.

Advertisement

Hide AdQuite a Good Time to be Born is a record of success, free of boasting or malice. Anyone with some knowledge of academia or the literary world will find it full of interest. Other readers may either be introduced to an agreeable vanished world or enabled to indulge in the pleasure of nostalgia. Either way, it is much more than quite a good book.

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND IPHONE APPS