Book review: OK, Mr Field, by Katharine Kilalea

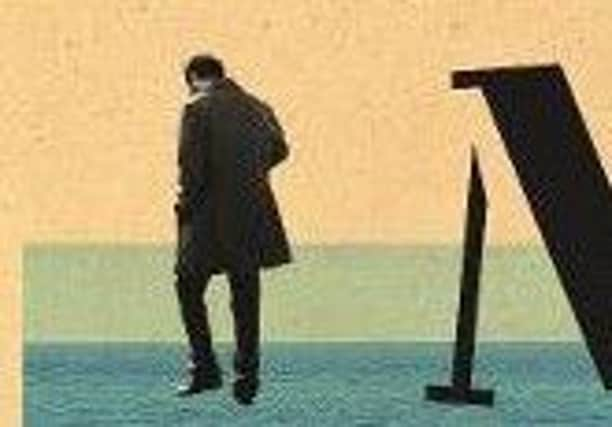

The protagonist (although that word’s literal meaning of “first struggler” or “first actor” makes it seem altogether inappropriate in this context) is a concert pianist who has injured his hand in a London train crash. On a whim, he decides to use his insurance payout to buy a house modelled on Le Corbusier’s stark modernist masterpiece, his Villa Savoye, in a foggy seaside resort outside Cape Town.

Once there, nothing happens, slowly. Field and his wife Mim go to the beach, where they barely speak. (“Are you sleeping? she said. And I said, Yes, tilting my hat lower to hide my eyes.”) One of their wordier exchanges concerns the house. Mim asks her husband why he likes it so much, to which he simply replies “I don’t know... I just like it, or admire it, or something.”

Advertisement

Hide AdField knows, however, that his relationship with the house is far more complicated than that. “Those were bland words, too fearful, too subtle to describe my feelings.” And indeed, as the novel progresses, the house almost starts to become, if not quite a character in its own right, then at least a stage set which seems to play a suspiciously active role in shaping Field’s moods.

Then, about a quarter of the way through, we have a happening: Mim leaves; or, rather, Field eventually becomes aware that her ever-lengthening absence might in fact become permanent: “All I knew for certain was that she’d driven off.” In another novel, this disappearance might have been just the incentive our hero needed to drag himself out of his slough of despond, but here it barely seems to have any impact on him at all. Rather than going out into the world to look for Mim, Field instead retreats further into himself, chasing his thoughts around the blank white walls of his house and fixating on tiny details of its design.

The only thing that does seem to animate him is Hannah Kallenbach, the elderly widow of the architect who designed the house. After a while, for reasons that are never made clear, her voice begins to find its way into his interior monologues: “What is there for me to do but go to bed? I thought. After all, I had no job, no wife, no child to take care of. Nothing, said Hannah Kallenbach, Absolutely nothing.”

It seems strange to speak of spoilers in a review of a novel with next-to-no plot, but I think it would be a shame to describe much more about how Field’s obsession with Kallenback unfolds, other than to say that it is expertly handled by Kilalea, to the extent that even when it plumbs the depths of improbable strangeness it is never less than believable.

An acute and thoroughly fascinating study of a mind on the point of collapse, OK, Mr Field is a wonderfully bold and incredibly assured debut, and when the words “eagerly anticipated second novel” inevitably find their way into the publicity material for Kilalea’s next book, they will be richly deserved.

OK, Mr Field, by Katharine Kilalea, Faber & Faber, 200pp, £12.99