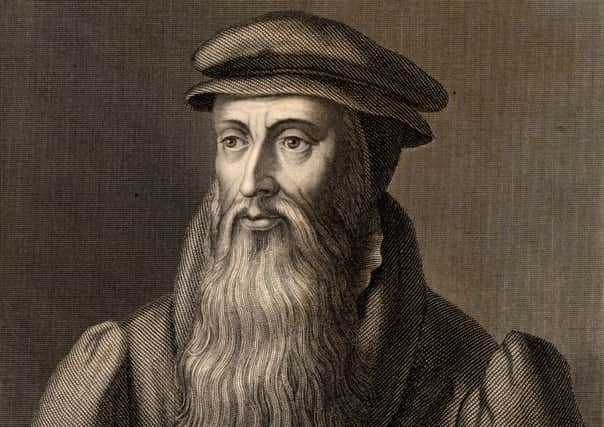

Book review: John Knox by Jane Dawson

John Knox

Jane Dawson

Yale University Press, £25

This book, by the John Laing Professor of Reformation History at Edinburgh University, is the very model of what academic biography can achieve. It displays all the virtues of the academy in that it is judicious and even-handed without being hobbled by caution. It brings to bear new source and archive material on its subject and is suffused with deep reading on the period.

Dawson goes back to John Knox himself – no mean feat given his subsequent centrality in Scottish culture. What emerges is a radically new portrait of the great reformer, which can and should be read by the general reader as much as the specialist.

Advertisement

Hide AdScotland has a problem with John Knox. His is a contested legacy, with part of the country seeing in him an intransigent killjoy and bullying misogynist, whose ideas ground the dour into Scotland’s soul. Other writers have looked especially at The First Book Of Discipline (1560, co-written with John Douglas, John Row, John Spottiswoode, John Willock and John Winram, the so-called Six Johns) which laid the groundwork for the Scottish education system, established the primacy of the congregation over the local landowners, and was remarkably open-minded about divorce and marriage against parental approval.

Very few people nowadays read Knox’s prose – and most will know only the notorious First Blast Of The Trumpet Against The Monstrous Regiment Of Women – but his History Of The Reformation ushered in a new kind of historical writing: personalised, indignant, sometimes sarcastic, utterly committed. There is a sense of personality in Knox’s history one struggles to find in Mair, Buchanan or Fordun.

Dawson carefully covers the major elements in Knox’s life – his conversion from Catholic priest and canon to Protestant reformer under the influence of George Wishart; his enslavement on a French galley; his dealings with Calvin in Geneva; his return to Scotland, where, to all intents and purposes, he enabled the Reformation; and his clashes with Mary Tudor, Mary Guise and Mary, Queen of Scots.

Knox’s experience in Geneva led to a double focus in the Reformation. It has to do with one’s own spiritual struggles and beliefs, but it needed to be grounded in political actuality. Knox was never a Nicodemist, putting private religious practice over the state’s relationship with religion. As Dawson wisely observes, one of the paradoxes of Knox’s career is the establishment of a national church out of “resistance groups” which thought of themselves as a beleaguered remnant.

The other major difference she highlights is that although the stereotype of Knox is of an inflexible individual whose self-confidence sheers into self-righteousness, the new sources she analyses reveal a far more conflicted man, often uncertain of his calling and prone to depression. His reliance on his wives, his “Edinburgh sisters” and particularly the friendship of Christopher Goodman has perhaps been underplayed in previous biographies. That Knox evidently struggled makes him, to my mind, more heroic rather than less.

Another area where Dawson provides some much needed clarity is, ironically, on Knox’s Scottishness. As she cleverly observes, Knox was around 45 when he returned to Scotland and had spent little of his active religious career in the country. He was mocked by Ninian Winzet for his English accent, and, as she says, “if, when he sailed from Dieppe in 1559, his ship had foundered, his career would form part of the radical wing of English Protestantism and would merit a footnote in French Huguenot history”. The persecutions of Mary Tudor and the chance to make a “reformed” nation under Edward VI were of equal consequence in Knox’s career to the events in Scotland after 1560.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere are some areas where Dawson’s account is perhaps slightly more conventional. No doubt Elizabeth was furious at Knox’s attack on female rule, and there is no reason to disbelieve in her anger. But, as AN Wilson has argued in his book on the Elizabethans, she learned the central lesson of the First Blast: that a female ruler was always in danger of being overshadowed by whichever other ruler she married.

It is a major strength of this biography that it takes Knox’s religion seriously. In many respects, when events turned out exactly as he had forewarned, this confirmed Knox’s sense of a prophetic and providential aspect to history. One cannot understand him without understanding that his mind was as much late Medieval as early Renaissance.

Advertisement

Hide AdThat Knox would nickname Secretary Lethington, a late enemy, as “Michael Wylie”, punning on Machiavelli, shows how far he was from being a circumspect tactician. Again and again in Dawson’s account, we see Knox making strategic mistakes. One might argue Scotland needed revolution rather than politicking at that point. What is without question is that Knox expected to die for his faith and was willing to do so.

Carlyle, in his great essay about Knox in On Heroes, Hero-Worship, And The Heroic In History, wrote “This that Knox did for his Nation, I say, we may really call it a resurrection as from death… The people began to live: they needed first of all to do that, at what cost and costs soever. Scotch Literature and Thought, Scotch Industry; James Watt, David Hume, Walter Scott, Robert Burns: I find Knox and the Reformation acting in the heart’s core of every one of these persons and phenomena”.

I can’t disagree. But Dawson shows how Knox was even greater through being weaker than we thought, and was as influential in England and Europe as in Scotland.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS