Book review: Eichmann Before Jerusalem

EICHMANN BEFORE JERUSALEM

BETTING STANGNETH

Bodley Head, 608pp, £25

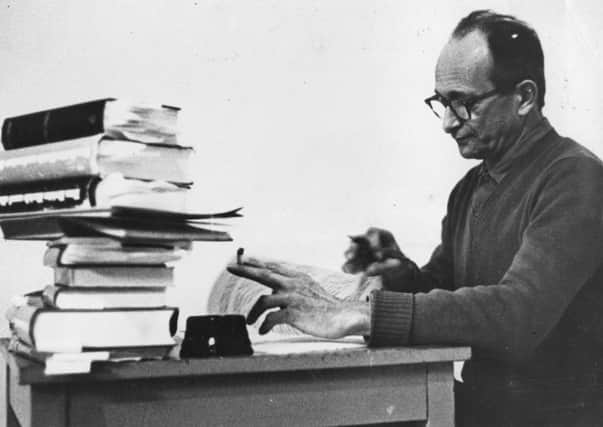

Ever since his capture in the early 1960s, Otto Adolf Eichmann, who was in charge of Jewish affairs during the Third Reich, has been the subject of unsettled and passionate controversy – centered, above all, on Hannah Arendt’s portrait of him at his 1961 trial. Her Eichmann in Jerusalem in many ways mirrored Eichmann’s own self-presentation. She insisted that, contrary to expectations, the man in the dock was not some kind of demonic Nazi sadist but a thoughtless non-ideological bureaucrat dutifully following orders and implementing the Holocaust.

Yet as Bettina Stangneth demonstrates, in his post-war exile Eichmann was almost the opposite: a passionate, ideologically convinced Nazi who, quite unlike a plodding functionary, boasted of his “creative” work. At one point he described the mass deportation of more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews as his innovative masterpiece: “It was actually an achievement that was never matched before or since.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe enduring image of Eichmann as faceless and order-obeying, Stangneth argues, is the result of his uncanny ability to tailor his narrative to the desires and fantasies of his listeners. Arendt was not the only one to be taken in, and Stangneth is able to present a more rounded picture on the basis of previously unmined archival sources, particularly Eichmann’s own compulsive notes and jottings made in exile, in conjunction with the elusive series of taped conversations known as the Sassen interviews. These were exchanges organized in Argentina by the Dutch Nazi journalist Wilhelm Sassen and attended by a small group of old Nazis and their sympathisers.

It is in these interviews and Eichmann’s own notes that he gave uninhibited vent to his version of the Holocaust and his involvement. While his Nazi audience wanted to either deny the Holocaust altogether or regard it as a conspiracy of the Gestapo working against Hitler and without his knowledge, Eichmann dashed their expectations. Not only did he affirm that the horrific events had indeed taken place, he attested to his decisive role in them. Hardly anonymous, he insisted on his reputation as the great mover behind Jewish policy, which became part of the fear, the mystique of power, surrounding him. As Stangneth observes: “He dispatched, decreed, allowed, took steps, issued orders and gave audiences.”

Like many Nazi mass murderers, he possessed a puritanical petit-bourgeois sense of family and social propriety, indignantly denying that he indulged in extramarital relations or that he profited personally from his duties, and yet he lived quite comfortably with the mass killing of Jews. This was so, Stangneth argues, because Eichmann was far from a thoughtless functionary simply performing his duty. He proceeded quite intentionally from a set of tenaciously held Nazi beliefs (hardly consonant with Arendt’s puzzling contention that he “never realised what he was doing”).

His was a consciously wrought racial “ethics,” one that pitted as an ultimate value the survival of one’s own blood against that of one’s enemies. He defined “sacred law” as what “benefits my people”. Morality was thus not universal or, as Eichmann put it, “international”. How could it be, given that the Jewish enemy was an international one, propounding precisely those universal values?

In the trial in Jerusalem Eichmann cynically invoked Kantian morality, but as a free man in Argentina he declared that “the drive toward self-preservation is stronger than any so-called moral requirement”. He had been a “fanatical warrior” for the law, “which creates order and destroys the sick and the ‘degenerate’” and which had nothing to do with humanist ideals or other weaknesses. From a surprising admission of German inferiority – “we are fighting an enemy who ... is intellectually superior to us” – it followed that total extermination of the Jewish adversary “would have fulfilled our duty to our blood and our people and to the freedom of the peoples”.

In addition to minutely examining unknown aspects of Eichmann’s furtive post-1945 life, up to his capture as Ricardo Klement in Argentina in 1960, Stangneth’s book contains numerous other revelations. She exposes the often shamelessly open post-war networks of Nazis (who actually dreamed of regaining power in Germany) and their sympathisers (especially within the Catholic Church). She documents the almost incredible lack of interest, inactivity, even cover-ups by the numerous groups charged with bringing Eichmann to justice. It now appears that by 1952, German intelligence services – and to some degree Jewish and Israeli bodies – were aware of Eichmann’s whereabouts, yet for various political reasons did nothing to apprehend him. Remarkably, Eichmann actually drafted an unpublished letter to Chancellor Adenauer proposing to go back to Germany to stand trial. Convinced of his blamelessness, he felt sure that he would receive only a light sentence and, like many other Nazis at the time, go on to live a comfortable German life. The story of Eichmann Before Jerusalem is thus also a tale of missed opportunities to hold the trial in Germany and create a genuine new beginning in an era that wished the dark past would simply go away.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdolf Eichmann may be dead, but the philosophical and psychological stakes surrounding him remain urgently charged and contested. As Stangneth notes, too often Eichmann himself has dissolved into the background while abstract notions of ultimate evil and everyday banality, the mechanics of genocidal bureaucracy and the imperatives of murderous ideology, are debated. Her comprehensive research brings the man and his circumstances firmly back into focus, and no future discussion of him will be possible without this book.