Book review: The Double Life of Laurence Oliphant by Bart Casey

The Double Life of Laurence Oliphant: Victorian Pilgrim and Prophet by Bart Casey | Post Hill Press, 300pp, £18

The subtitle describes Laurence Oliphant as a Victorian Pilgrim and Prophet, and a note below calls his life “incredible”. This is not a good recommendation. An incredible life wouldn’t be worth reading. In fact, Oliphant’s was unusual, even bizarre, but by no means unbelievable. Soon after his death in 1888 a biography was written by his cousin, Margaret Oliphant, and there is also a clear and detailed account of his career in the Dictionary of National Biography.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Double life” is a bit misleading too, because it suggests that one side of the life is hidden. “Divided life” would be more accurate, for the interesting thing about Oliphant is that he was, on the one hand, a successful man of the world as traveller, journalist, author, diplomat and, briefly, MP for Stirling Burghs, and on the other, a mystic and investigator of the spirit world, who was, as the DNB puts it, kept for some time as “a spiritual slave” in the cult founded and led by a charismatic American called Thomas Lake Harris.

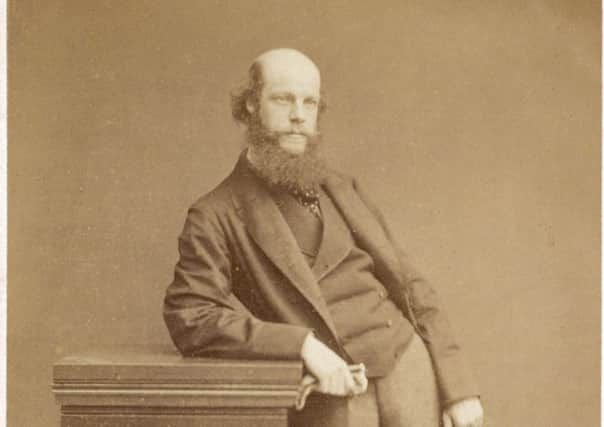

Laurence Oliphant was born in Capetown in 1829. His father, a member of the Scottish family formerly distinguished for their loyal Jacobitism, then became Chief Justice in the new British colony of Ceylon, and Laurence spent his early years there. He travelled and wrote books about his travels, became a foreign correspondent for the Times, covering the Crimean War, and took part in diplomatic missions in the USA, China and Japan as an aide to the Earl of Elgin. He was popular in London society, became a friend of the Prince of Wales, wrote a successful satirical novel and was elected to Parliament, where his maiden speech – about Fenians – was not a success. So far, nothing unusual for one of his class and background.

His parents were Evangelicals and from boyhood Laurence was much concerned with the state of his soul, a preoccupation which didn’t prevent him from having an active social and sexual life. He flirted with Spiritualism, even before meeting Harris, who was in London preaching his new spirit religion. Harris, like so many cult leaders, was himself part-mystic, part-phoney – also an intermittently successful businessman. He taught that by practising “right breathing”, the Breath of God would enter you. He also taught that evil spirits were everywhere, ready to assail and lead astray the ungodly. Casey’s account of the cult is full, even-handed and grotesque. You wonder how anyone of sense could fall for it. But Oliphant and his mother did, and for the first year of their discipleship were forbidden to speak to each other. The DNB’s “spiritual slavery” sounds right. It is evident Harris was at least three-quarters a rogue and charlatan, but also that he was a very persuasive one. Eventually, Oliphant broke away – to be reviled as a traitor. He had also wed, though his marriage seems to have been unconsummated, and he returned to journalism, covering the Franco-Prussian War, the Siege of Paris and the Commune. Oliphant then became an early Zionist, helping to establish one of the first Jewish settlements – of Romanian Jews – in the Holy Land. He wrote several mystical works, and when widowed, returned to England, wed again, before dying at Twickenham, having just finished a book entitled Scientific Religion. His second wife subsequently helped to expose Harris as a fraud. It’s certainly an interesting life, and Casey has written an interesting book, admirably deadpan in its treatment of the Harris Community, less assured in its picture of British society, politics and imperialism. Oliphant’s life was certainly remarkable, but not as unusual as the bare account one can offer in a review may suggest. Awareness of the “spirit world” was common in the 19th century. One thinks of that strange Scots-Irish American mystic, Francis Grierson, and of Calvin Stowe, Presbyterian minister and husband of the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, supposedly visited, and on occasions attacked, by demons from his childhood onward. And there were lots of other cults like Harris’s in the USA. Strange times, but ours will doubtless seem equally strange a hundred years on.