Book review: A Decent Ride by Irvine Welsh

A Decent Ride

By Irvine Welsh

Jonathan Cape, 496pp, £12.99

In a culture increasingly mired in debate about the limits of acceptable self-expression – the sanctity of free speech versus the effects of “hate speech”; the debatable appropriateness of “trigger warnings” in education and academia; even the development (and swift withdrawal) of a “Clean Reader” app that removed swear words from books – it’s rather bracing to read a writer as blissfully unconcerned with political correctness as Irvine Welsh.

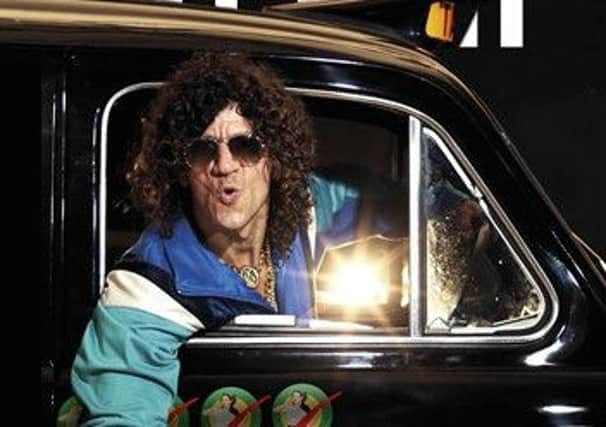

Well, perhaps he is concerned with it, in the sense of being certain to affront it at every turn. Trigger warnings for A Decent Ride, his tenth novel, would have to prime readers for substance abuse, child abuse, elder abuse, prostitution, pornography, incest, and various forms of corpse desecration including necrophilia. What would the Clean Reader make of Irvine Welsh? It’s tempting to imagine them in a sort of duel, like when Garry Kasparov played against the chess computer. Then again, would the Clean Reader even recognise “ma hole” – the prime motivator in the life of this novel’s protagonist, taxi driver, drug dealer and sex obsessive Terry – as an obscenity? What about “gantin on ma hole”, which is the state to which Terry is consigned when his extremely active sex life is brought to an unceremonious end? Or “Auld Faithful” – the most prized part of Terry’s anatomy, which even gets its own shot at narration duties, in chapters typeset to imitate its shape? (If you’re having trouble imagining this, picture an obscene version of the bit in Alice in Wonderland that’s printed in the shape of a mouse’s tail.) Does the Clean Reader even know how to register offensive typography…?

Advertisement

Hide AdProdigious endowment is one thing that Terry shares with the novel’s other pivotal figure, Jonty, a young painter and decorator variously described as “slow”, “no aw thaire” and “dippit”. Unwittingly on Jonty’s side, they also briefly share Jonty’s girlfriend, Jinty, until she becomes mysteriously unavailable to both of them. That the sparky and streetwise Jinty should be in a relationship with someone unworldly enough to refer to her cocaine habit as “funny stuff up the nose” is unsettling; but so multifarious are the forms of depravity with which Welsh surrounds them that Jinty and Jonty might ultimately represent the novel’s most positive depiction of a long-term relationship.

If Welsh does sometimes seem to be pushing his characters to lurid extremes just to see how much the reader can take, there’s a solidity and even a charm to his cast of characters that grounds this novel in an unexpectedly persuasive emotional reality. These people never feel like mere mouthpieces for Welsh’s own worldview; they are fully and sympathetically realised, and their stories make indirect but potent points. In Jonty we see the muddled moral awareness of a child, aware of “badness” in his life but ever hopeful that a comforting friend or an order of Chicken McNuggets will make it go away. His beloved Jinty, vividly drawn enough to be a poignant absence when she departs the narrative, becomes a symbol of individual frailty and cruel fate, her misfortune foreshadowing Terry’s own.

Another of Terry’s conquests, playwright Sal, makes a brief appearance but a solid narrative point: that intellect and money do not ensure smooth sailing through life, and that emotional disarray is very far from being the sole preserve of the ill-educated or economically disadvantaged. And via Terry himself – a character with whom he has been conjuring since his 2001 novel Glue – Welsh evokes not only a state of crippling obsession, but also the haphazard generosity and basic goodness of an ostensible degenerate. In a sense it’s Terry – Kind Terry, as Jonty calls him – who is the book’s “decent ride”.

Less successful is the element of the narrative concerning Terry’s friendship with egotistical reality TV star Ronald Checker. Perhaps it’s that a novel that finds so much charisma and grotesquerie in its array of “ordinary” lives simply doesn’t require an extra narrative thread, and certainly doesn’t need to launch itself at the easy satirical target of shallow celebrity.

There’s also the fact that Welsh, although an American resident of some years’ standing, is still clearly at his most content and lucid as a writer when he’s playing with Scottish dialect and Scottish concerns. The independence referendum, Edinburgh’s tardy trams, the turmoil and erotic opportunities thrown up by the summer festivals, and the deathless Hearts/Hibs rivalry all take their part in forming the backdrop of Terry’s life – and these sly, pointed references say more about contemporary Scotland than the more obvious golf-and-whisky stereotypes that are lampooned in the course of the Checker storyline. In the end, like the cheeky taxi driver it depicts, A Decent Ride takes a few too many superfluous diversions; but if you’ve a strong enough stomach for it, the chat along the way makes the trip more than worthwhile.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS