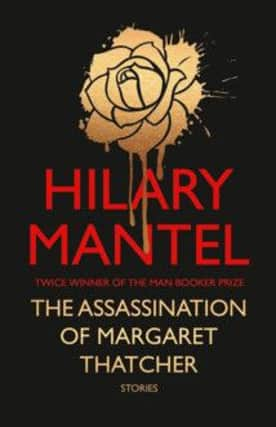

Book review: The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher

THE ASSASSINATION OF MARGARET THATCHER

HILARY MANTEL

4th Estate, 256pp, £14.99

She pursues a host of difficult topics: misogyny, adultery, accidental infanticide, a fatal case of anorexia, dead yet intrusive fathers and, in the disturbing title story, the assassination of historical figures one had always assumed were not assassinated. Despite the phalanx of themes, however, one can’t help feeling that Mantel’s imaginative world is all of a piece.

How so? Mantel’s artful use of various classic storytelling gambits no doubt reinforces one’s sense of this all-of-a-pieceness: her Brontë-esque preference for knowing, if not cynical, first-person female narrators; the crisp, droll narrative idiom; and her abiding curiosity about what might be called the crises of bourgeois sociability – disturbed and/or misfiring relationships between hosts and guests. Unexpected meetings and domestic matchups are a favourite fictional jumping-off point. More than one tale hinges on the action of a solitary but possibly foolhardy woman who, hearing the doorbell, invites the strange man she discovers outside to come into her flat. And, yes, she will learn, soon enough, to rue her hospitality.

Advertisement

Hide AdPlot is frequently subordinated to dialogue in Mantel. Two ill-assorted characters – usually a man and woman who have never met before – bicker with each other from unanticipated intimacy. Usually,the male figure does little but boast and subtly threaten; the woman seems mostly alienated, a bit mad even, and only becomes more so. (It’s not clear, by the way, that Eros ever has anything to do with these Beckett-like exchanges.) Conversations peter out into muffled strings of cliché and nonsense; loony-bin theories go unchallenged; and, by the story’s end, one fears the worst.

But, most important, all of Mantel’s stories share a similar design on the reader. One gets the feeling she wants both to frighten us and make us laugh. She’s like an old-fashioned spirit-medium of sorts: a brusque, mischievous, Madame Arcati-like purveyor of uncanny moments. She transports us somewhere else. And she seems to be having great fun with it too. Ubiquitous indeed are her spooky little fillips of what-have-you that mess with your head.

In time, one learns to expect them. They could be unfamiliar word or bizarrely weighted phrase; a maddeningly opaque piece of dialogue; an absurd but sinister item of fictional décor (the boiler man’s mate carrying a telescopic rifle, for example). You pull up sharp to see what’s what, but at that point she’s already got you. Your attention has been smoothly locked in. Critical scepticism be damned: you will be reading this story to the end.

Whatever that hook is will be different for different people. For me, it came in the very first story, when the narrator, living as a virtual recluse in a stifling, marble-staircased apartment in Jeddah describes her habit of wandering daily about it as if in a fugue state, with a can of insecticide in her hand. “Sometimes I sprayed it as I walked, and it fell about me like bright mists, veils.”: by the time I’d got to the “bright mists” – an image at once rhapsodic and wacky – it was as if I could smell the story. Everything had turned sweet and choky and malign. And, yes, to my no doubt depraved sensorium, also spookily irresistible.

Similarly, in the title story, a chilling, fable-like “counterfactual” set in 1983 – in which a sniper plans to assassinate Margaret Thatcher from a window as she leaves a private hospital where she’s just had eye surgery (Thatcher did have exactly such surgery in 1983) it’s the noirish references to her handbag, or the way in which the nameless assassin’s contemptuous mention of the way the Mrs T “toddles” about in public ghoulishly conjures up the Iron Lady in all her lower-middle-class glory.

Mantel is such a funny and intelligent and generously untethered writer that if you’re intelligent and quirky enough to read this book, she has quirks enough of her own to match you, if not double the bet against you.