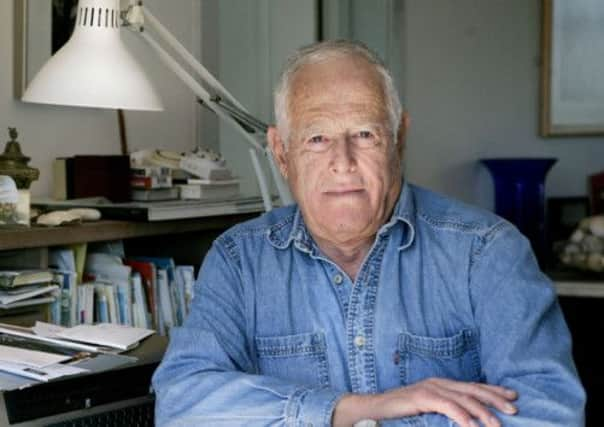

Book review: All That Is by James Salter

All That Is

By James Salter

Picador, 290pp, £18.99

I remember reviewing one for The Scotsman towards the end of the 1970s. The title was Light Years and I have forgotten everything about the story, setting and characters, but its bittersweet flavour and its elegant, somewhat self-indulgent tone. There was a touch of dandyism about it. An editor at his London publisher told me he was rather a difficult author, and I wasn’t surprised.

All That Is has the same tone of voice, detached, amused, somewhat languid. Descriptions are brief and vivid, conversations often sharp. Much that happens seems to be improvised, as if the author started the book with only a vague idea of where he was heading. This may not be the case, but it’s what it reads like. There are lots of loose ends. Characters who look as if they are going to be important, drop out. Some of them die, quite abruptly; others merely fade away. One appears in the opening chapter, and doesn’t return till the end of the book. His re-appearance has no great significance; it’s just pleasant. All this is oddly attractive.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt’s also lifelike. Some novelists, great ones among them, impose a pattern. They follow the figure in the carpet. They give their characters the sort of shapely life that life itself rarely serves up. Life is, for most of us, one damned thing after another. That’s how it is for Salter’s hero, Philip Bowman, even though many of the damned things are enjoyable. He is a man with an agreeable relish for experience: for women, for his work as an editor in a respectable New York publishing house, for foreign travel, meals, conversation, painting, scenery and the rhythms of city life. He served in the navy, in the Pacific against the Japanese, experiencing kamikaze raids, and came through. He comes through most things, even the fraying to the point of separation of a marriage that began in mutual love. For most of the book he seems a good man, though one capable of acts of callousness, even cruelty. There are sections of the novel from which he is absent, but most of the time it is his story Salter is telling, engrossingly, yet in detached manner. Bowman is capable of surprising the reader, because we never really know him, which is true to life, and perhaps he doesn’t, for all his acquired air of authority, ever really know himself; again like most of us.

There are fine scenes set in Virginia, in old East Coast Wasp America, where the assurance of the characters, among them Bowman’s father-in-law, allows them to pretend that their country is moving away from them. Or perhaps they just don’t notice. This is a common experience. Things go along as you expect them to, and then one day you notice that everything is different. Salter rather beautifully captures this. Late in the novel, Bowman, the fiction editor, realises that “The power of the novel in the nation’s culture had weakened. It had happened gradually, it was something everybody recognized and ignored.” So it goes, as Kurt Vonnegut, who recognised this truth and found it depressing, would have said.

Salter is very good at showing the inconsequentiality of so much that happens. You build up for the big emotional dramatic scene, and later may find yourself wondering what all that was about. There are love affairs in the novel, which are just about sex, and then they are over, and that’s that. You can’t remember what all the fuss was about. Salter is good on the selfishness and carelessness of the rich – there’s an echo of Scott Fitzgerald here – and the neediness of the poor; he understands the strangeness – the unavoidable strangeness – of other people. Of one character he says: “He could look on his life as a story – the real part was something he’d left behind”; another Fitzgerald rhythm there. There is a story here, indeed there are many stories, and mostly interesting ones, but there is no plot. There is no plot because the novel doesn’t need one. You read each section because it is sufficiently satisfying in itself, with no great curiosity for the next one. There are characters and settings you may wish the author would linger on, but they are carried away on the river of life. And why not? Most of those one encounters are ships that pass in the night. If VS Pritchett found the germ of some of his stories in the sight of a couple in a bars who set him wondering what one saw in the other, Salter shows us how little of what we once thought mattered greatly comes eventually not to matter at all. This is quite comforting and at the same time exhilarating. One of the many attractive things about this novel is that it deals in pleasures. One of the true tings is the reminder of how these pleasures fade, to take on a new life – if there is any new life – only in memory.