Artist Ilana Halperin reflects on the scientific and the personal

When she reached 30, the artist Ilana Halperin travelled to the Icelandic island of Heimaey to visit the Eldfell volcano.

Eldfell appeared in the world in 1973, the same year as the artist. Perhaps for Halperin, the sense that, in geological terms, the volcano was an extraordinary youngster helped mitigate the sense of human years passing.

Advertisement

Hide AdA decade later, Halperin went back again. The first time she had pocketed a piece of crystal she had found on the slopes. On her second visit she picked up an agate from the red lava flow.

Both stones are pretty humble but now find themselves in splendid cases in the grandeur of the National Museum of Scotland, where Halperin has received the museum’s inaugural Artist’s Fellowship.

They are there, not because they are particularly extraordinary, but because if you stop for even a minute to think about it, everything in the discipline of geology is extraordinary.

The artist has placed her finds next to other objects from the museum’s collections, each one created by the collision of mighty forces: tektites from Australia, formed by the material ejected during a meteorite impact; Egyptian desert glass, formed in the heat of a meteorite explosion above the Earth. Scientific estimates put the age of some desert glass at about 26 million years old, which certainly puts your 30th birthday in perspective.

Halperin’s new exhibition, The Library, is full of such reflections. It brings together the scientific and the personal, the broad sweep of planetary processes and the daily account book of accumulations and losses.

The artist, a New Yorker, came to Scotland to study on the Master of Fine Art course at Glasgow. But she stayed in Scotland after she graduated in 2000. Among her reasons, the nation’s intellectual resources and its historic status as the birthplace of modern geology.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhen I first encountered her work, the year she graduated, Halperin’s interest was positioning the human lifespan against the geological one. I remember a photograph of the artist curled among the fossilised tree stumps in Glasgow’s Fossil Grove, and an image of Halperin, dressed in red cagoule, boiling milk in a geothermal spring for her breakfast coffee.

They were simple acts that seemed to express, with profound economy, the strangeness of our human encounters with the ground we stood on.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn the years that have followed, her research has led into more nuanced concerns. Her research into the working lives of vulcanologists and the plight of communities in volcanic regions became a meditation on personal loss.

A current exhibition, STEINE, at the Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité in Berlin brings together rocks and minerals with the strange stones produced by the human body.

Increasingly Halperin’s art brings together human ways of making with the kind of geological actions that built the world around us like the laying down of mineral deposits and the creation of stalactites and stalagmites. The correlation between artistic processes and natural ones is not new, but Halperin goes to great lengths to use them as practical methods as well as elegant metaphors and she doesn’t disguise the elaborate artifice and mechanics required to get there.

Back in Iceland last year she submerged laser cut wooden stencils for 12 months in the runoff of the thermal plant which feeds the famous mineral rich waters of the Blue Lagoon.

After a year underwater the silica mineral deposits have created a gorgeous crystalline confection now suspended in a mirrored case. A lot can happen in a year, explains the accompanying panel, “a person can form and we can form geology.”

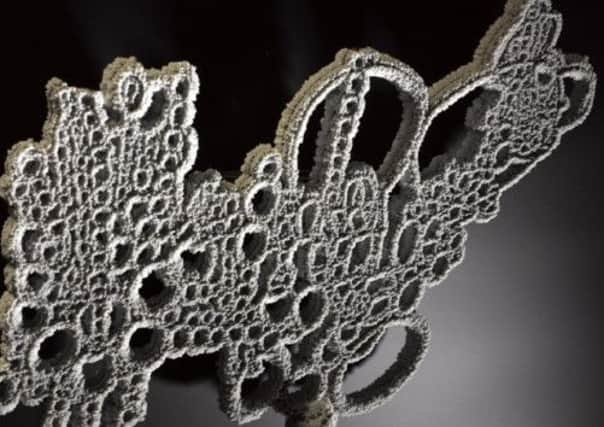

In France, Halperin worked with the Fontaines Pétrifiantes in Saint Necatire in the Auvergne where seven generations of the same family have made a living harvesting carbon-rich springs to create sculptures like limestone stalactites. In nature these grow at a centimetre a century, but Eric Papon’s family business can now do the same in a year. Halperin has made seven fat “corals”, their stumpy fingers waving liked beached sea creatures.

Advertisement

Hide AdSo how well do these stories sit in their museum context? I’m a rare dissenter when it comes to the National Museum’s massively popular refurbishment.

I feel that in stripping out it’s grand central space at least part of the baby has gone the way of the bathwater and, in contrast, the visually crowded spectacle of some of the rooms makes it hard to think or to decipher what stories the museum is trying to tell.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut The Library (so-called because samples of the mineral mica are descried as books) looks splendid in its setting. Halperin’s spare, sensitive installation is so elegant and her narratives so seductive that they might act as an exemplar of how to present scientific collections. She works gently with what is there. Like that meteoric material, each case is a condensed explosion of related ideas. Admittedly these are personal and subjective, but their poetry does not necessarily mean that they are scientifically flawed.

Her aesthetic sense is keen and the standards of installation are exquisite. Objects are mounted on simple brass stands with jewel-like precision. The cabinets are a wily combination of museum case and sculptural plinth that chime with the arts and crafts tiled floor beneath.

It’s a very common idea to ask artists to respond to objects in museum collections for temporary exhibitions or for their artwork to be situated among museum exhibits.

Halperin was perfect candidate for a fellowship. Hopefully the museum will continue its work with artists.

To invite an artist to create permanent displays is another thing altogether. That’s just what Halperin is doing in Shrewsbury, Darwin’s birthplace, where she has been appointed artist/curator for geology at the Music Hall. On the strength of The Library she is more than up to the task.

• Until 29 September