Art reviews: RSA Annual Exhibition 2019 | Mary Cameron: Life in Paint

Art reviews: RSA Annual Exhibition 2019, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Mary Cameron: Life in Paint, City Art Centre, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe RSA’s new president, Joyce Cairns, is the first woman to be elected to that office. It’s not before time. It is the academy’s bicentenary in 2026. The new president has also overseen changes straight away. Most immediately, after a decade as a semi-curated show, this year the annual exhibition has reverted to its longstanding form of work by academicians balanced by works selected from an open submission. Almost 2,000 works were submitted by around 1,200 artists. Impressive figures, but online submission does make the task less unwieldy than it used to be when every single work submitted had to brought in and paraded in front of the selection committee. From this submission around 150 were selected. With a similar number from the academicians, the total is well over 300 and there are another 60 in the two galleries devoted to architecture.

In spite of these numbers the show does not seem crowded, even though it includes a good number of very large works. A magnificent black silhouette of a winter tree by Kate Whiteford commands one end of the central gallery, while two big panels by Glen Onwin, created from traces left by evaporation but resembling ominous, crimson skies dominate the other. Nearby Aberdeen and Angus is a large diptych by Francis Convery, convener of the main exhibition. It is a rich and intriguing mix of paint and collage. Stings to be Gathered by Julie-Ann Simpson, also a diptych, is a rather beautiful composition principally of leaf forms. Nettles provide the stings. There are more stings in a magnificently outspoken work by Calum Colvin. He combines images and slogans to make his views on our current politics quite clear: “Leave.con,” or “Brexit: Every cloud has a sillier lining.” Past president Arthur Watson also uses words, wonderful Scots words for snowfall and nightfall, 25 of them rendered in smoky black, each in its own frame. Robert Burns, nearby in a beautiful painting by Adrian Wiszniewski, would have approved. Paul Furneaux’s North Window is a large composition of Japanese woodblock prints mounted and lacquered to make a lovely abstract object. Elsewhere, James Vass uses the patterns of woodblock very differently in his geometrically composed Lighthouse.

There is a variety of figurative works too, both painted and sculpted. Kevin Dagg’s Paradise Lost carved in wood, for instance, seems to have strayed from a Gauguin painting while the girl in Heather Nevay’s The Bad Girl’s House suggests rebellion rather than contrition. Jessica Harrison appropriates a Coalport figurine, the ultimate china doll, and reclaims it for feminism by glazing it in jet black with blazing, angry eyes. Black is the colour of Kenny Hunter’s Black Swan, star of the show. A wonderful swan in painted bronze on a pointedly unfinished base, it is an eloquent image for our time. The black swan was a philosophical oxymoron until it was confounded by a real black swan turning up in Australia. By extension, a black swan event is something that shouldn’t be possible, but happens nonetheless, like much in contemporary politics. Jake Harvey’s elemental forms in polished stone make a nice contrast with the ephemeral delicacy of Jacki Parry’s scarlet paper flowers, Musas Rosas. Patricia Cain’s three big panels apparently from a larger series called George’s Walk, shift painting of foliage towards abstract expressionism. Jane Embury’s Great Faith is purely abstract leading from surface into dark and shadowy depth. Da Hee Lee explores the relationship between abstraction and music by rendering a Bach Prelude in patterns of dots and colours reminiscent of Mondrian’s Boogie Woogie pictures. Sam Shendi suggests similar echoes in Cityscape, a sculpture in a brightly coloured geometry of steel in box sections.

Nature is celebrated directly Ian Westacott’s etching, the Brahan Elm, one of his wonderful portraits of ancient trees, and in Derrick Guild’s beautifully executed Puffin and Pelican, recreating a piece of Victorian nature study, while Henry Kondracki paints a simple, sunny view of the Water of Leith. Catharine Davison’s Oxgang’s Garden, Summer Still Life is another celebration of a fresh green world. Jayne Stokes’ Pocket Editions is a set of dainty landscapes painted on the inside of matchboxes. There is also the fantastic in Margaret Smyth’s La Sirene, a girl in a balloon skirt floating up in a balloon, and the bizarre in Ian Howard’s portraits in elegant renaissance style of the unfortunate Isobel Gowdie.

As always the RSA Annual also includes memorials to members who have recently died. This year Philip Reeves and Willie Rodger are commemorated with memorial shows to remind us of what we have lost. There is much else to see and do not forget the architecture. It is a vivid reminder of just how busy and creative our architects are.

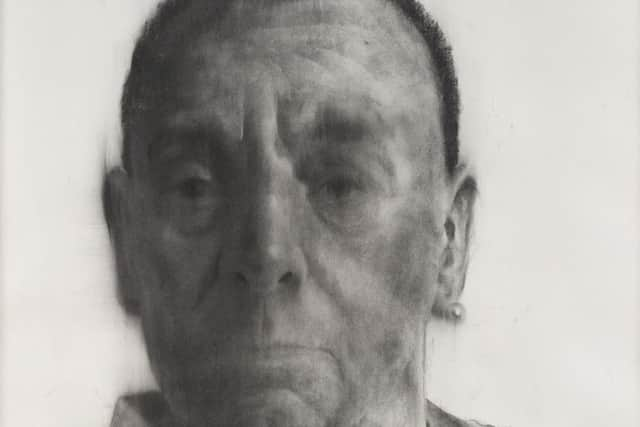

As we celebrate the first woman president of the RSA, a letter in the Mary Cameron: Life in Paint show at the City Art Centre is a reminder of just how much the RSA dragged its feet in recognising our women artists in the past. The letter is to the artist from John Lavery, warmly supporting her candidacy for the Academy. It is dated 1911. She had first been nominated in 1901, but it was not till 1940 that Phyllis Bone became the first woman to be elected RSA. There was no rule against women members – it was simply gross prejudice. Justifiably, Mary Cameron evidently felt like Jessica Harrison’s black china doll with blazing eyes. But Lavery was right. With an accompanying book by curator Helen Scott, this exhibition makes a substantial addition to the story of Scottish art.

Born in 1865 into the Cameron family, whose fortune was made by the patent steel nibs of Waverley pens (her brother was actually christened Waverley), she studied at the Trustees Academy and in Paris and subsequently proved herself much more than a rich dilettante. Precise and beautifully drawn watercolours of vanishing old Edinburgh – Last of Canonmills Village from 1893, for instance – demonstrate real accomplishment, but by her own account, it was Velazquez who was her great inspiration. His example is seen in a striking portrait possibly of her sister-in-law Margaret and in 1900 it took her to Spain where she copied his work and later that of Goya. A gifted linguist, she evidently became quite at home, so much so that she gained privileged access to the matadors and picadors behind the scenes in the bullrings. She studied the anatomy of the horse in Edinburgh and it was the horses of the picadors gored and bleeding from the bull that inspired her most remarkable paintings, works whose graphic immediacy shocked her audiences. She exhibited regularly in France and her Mute Martyrs of the Bullfight was used by the French government in a campaign against bullfighting. More acceptably she painted accomplished large-scale scenes of Spanish genre much in the manner of the early Velazquez. She also painted the Spanish landscape and was a particularly gifted painter of portraits. Her painting of Mrs Johnston, for instance, is a superb study of age, while her grand, full length of Mrs Blair and her Borzois could more than hold its own with the best work of any of her male contemporaries. Duncan Macmillan

RSA Open until 11 December; Mary Cameron until 15 March