Art reviews: Pin-Ups: Toulouse-Lautrec and the Art of Celebrity | Conversations with Paolozzi | John McLean: The Boston Pictures, 1982

Pin-Ups: Toulouse-Lautrec and the Art of Celebrity, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Conversations with Paolozzi, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdJohn McLean: The Boston Pictures, 1982, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh *****

Toulouse Lautrec and the Art of Celebrity is, as the title suggests, primarily devoted to Toulouse Lautrec. A few of his fascinating contemporaries in fin-de-siècle Paris are also added in, but the subtitle, the Art of Celebrity, is a bit too 21st century. Celebrity is certainly not a modern invention, but it has a new meaning. Celebrities in the modern world are almost a separate species from us ordinary humans. That wasn’t the case in Paris in the late 19th century. The people who provided Lautrec with inspiration and subject matter in some of his finest work were stars of song and dance in the café-theatres, but not celebrities in the modern sense. A better title might have been Lautrec and the Art of Publicity. The most striking things on view here are posters, works of art certainly, but advertisements and ephemeral. They are lithographs, cheap to produce and capable of big print runs. It was advances in colour lithography, a commercial process, that made them possible. The most striking thing seeing these well-known images is also how big they are. Lautrec’s famous Moulin Rouge: La Goulue poster is nearly two metres high. Others are a metre and a half. They are billboard posters, printed in thousands on cheap brown paper. They were never intended to survive. That any have done so is a miracle.

Some of Lautrec’s best loved – and also most effective – images are here. The Moulin Rouge: La Goulue, for instance, was a poster for the eponymous establishment and its star, the dancer La Goulue. She high-kicks and shows us her bottom in lacy, knee-length bloomers while her co-star, the contortionist, Valentin, shimmies across the foreground. Equally familiar is Reine de Joie. A girl with a cynical air kisses a balding old man on the nose. Reine de Joie, a slang term for a prostitute, was the title of a novel the poster advertised. This is a daring image of the demi-monde – the world at once seedy and glamorous that became both Lautrec’s milieu and his subject matter.

Japanese prints were a vital inspiration. He and others too, most notably Pierre Bonnard whose Revue Blanche poster is a star, all learnt from the Japanese a new, stylish visual economy with bold, spatial elisions and text and design closely integrated. Publicity hitherto had been either heavily or entirely textual. Here there is still text, but instead of prim typeface, it is casual, fluid and ornamental. Maximum visual impact is the aim and this there is in spades, not just with Lautrec and Bonnard, but with others like Steinlen’s wonderful poster for the Cabaret du Chat Noir. Later, British artists like JD Fergusson joined the fun. They are brilliant, but a bit of a digression here, for what Lautrec represents above all is the new partnership of artists and publicity in which modern advertising was born.

The stars of this world of theatre and cabaret appreciated the work of the artists they and their managers employed to promote them and so there were other spin-offs. Lautrec made two sets of lithographs for Yvette Guilbert, for instance, the second in advance of her appearance on the London stage which also coincided with a one-man show of his own work, thus identifying closely artist and subject in the public mind.

Jane Avril high-kicking at the Jardin de Paris is another Lautrec favourite image. Indeed she was a frequent subject and she said of him “It is more than certain that I owe him the fame that I enjoyed dating from the first poster he made of me.” Thus she recognised at the moment of its birth the power of this new alliance of art and advertising to create reputations – as we have later learnt, if need be, out of nothing at all.

Advertisement

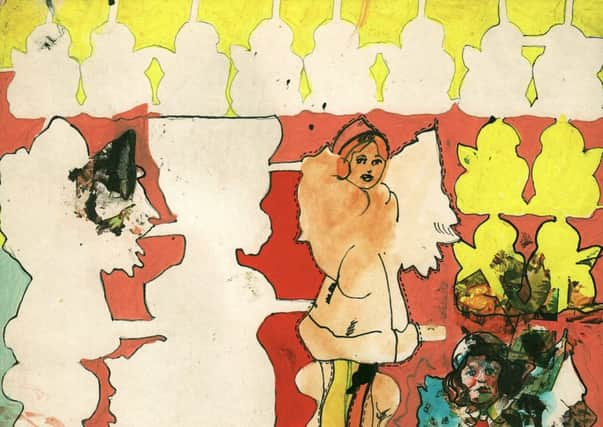

Hide AdDownstairs in the RSA building, in Conversations with Paolozzi 15 artists have been invited to make work “in response to” the work of Eduardo Paolozzi. I generally avoid work produced by that formula. It produces self-important art while the verb “respond” suggests we are too much in awe of artists to expect them to do anything as self-effacing as simply pay homage to another artist. In this case though, most of these artists have done just that. In almost all the statements that accompany the works there is a note of genuine homage to a great artist. Doug Cocker, for instance, talks of his “fecundity and breadth of mind.” Michael Agnew calls him “a man of few words, but underneath driven by a creative reactor not short on fuel or imagination.” Michael Docherty calls him “a warm, generous and thoughtful artist.” Others too speak of his generosity, especially towards students. And as real admiration for Paolozzi comes through these words, so too it is visible in many of the works they accompany. In two screen-printed textile banners, for instance, Alfons Bytautus pays homage to his pioneering work in screenprinting, but also to the textile designs that he produced in the 1950s. Cocker’s vivid and brightly coloured, totem-like wooden figures pay homage to Paolozzi’s use of colour, but also of assemblage. Paul Furneaux evokes Paolozzi’s use of pattern and also occasionally of woodcut too in his beautiful mounted woodcut, Untitled Pink and Black. Aptly, too, Michael Vissochi has invoked the artist and his work in The Tomb of Eduardo Paolozzi. (To declare an interest, this exhibition accompanies the publication of Paolozzi at Large in Edinburgh, a collection of essays on the artist’s work around the city and edited by Carlo Pirozzi and Christine de Luca, to which I have contributed.)

Paolozzi was an expatriate Scot who pursued his career in London. John McLean is another. The Boston Pictures at the Fine Art Society is not a show of recent work, however, but of beautiful paintings done nearly 40 years ago. Left rolled up in a Boston studio in 1982 when the artist couldn’t afford to bring them home, they were more or less forgotten. Recently, however, when the studio was cleared by a small miracle they were recovered. Now a group of them makes a wonderful show. They reflect a key moment in the artist’s career as he turned towards a truly lyrical abstraction. Big brush-mark shapes dance across the canvas. The canvases are unprimed, but usually tinted with a thin transparent colour while the shapes that move across them have more substance. Their thicker texture reflects the actions that produced them, so that the movement is not just in the open patterns that he uses, but is also captured in the frozen moment of his hand in their making. Add the play of luminous colour and it is as close as you can get to visual music. Exquisite, it is wonderful that they have been recovered. - Duncan Macmillan

Pin-Ups until 20 January; Conversations with Paolozzi until 28 October; John McLean until 10 November