Art reviews: BP Portrait Award | Scottish Portrait Awards | Marine Hugonnier: Travel Posters

BP Portrait Award, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh ***

Scottish Portrait Awards, Glasgow Art Club ***

Marine Hugonnier: Travel Posters, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ***

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn November last year, the Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland announced that, after 30 years, the current BP Portrait Award show at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery would be the last. Their official statement read: “We recognise that we have a responsibility to do all we can to address the climate emergency. For many people, the association of this competition with BP is seen as being at odds with that aim.” They are surely right, though the “many people” formula suggests public pressure rather than tender conscience. In the Middle Ages you could expiate your sins by buying an indulgence, or even building a church and paying priests to pray for your soul. On the face of it, modern day corporate sponsorship is not so different, although BP probably wouldn’t acknowledge any sins that need atonement.

It might seem that rejecting BP’s sponsorship is a token gesture, but if it hadn’t been worth it for the polish it gave their image, BP would never have put their money into this annual show. It has always been popular and BP’s name is right up front. The show generated many column inches and it reached parts of the public other shows never could. The reason? Just because portraits are human, I think, or at least that is the premise and the promise. I am less sure about the outcome.

I have said it before, but it remains pertinent to such a big enterprise: the painted portrait survived the challenge of photography until the advent first of colour, then of scale. That was quite recent, but once the photograph could challenge a painting in likeness, in full colour and on a big scale, artists didn’t know where to turn. Their response is generally pretty lame. They don’t know how to beat photography so mostly they join it.

Here, for instance, the first prize went to Imara in her Winter Coat by Charlie Schaffer, a painting of a melancholy looking woman in a faux-fur coat. The artist claims that he “doesn’t aim to capture the essence of the sitter, nor create a likeness.” You do wonder how he ends up with a portrait, but no matter what he says, this is really a photographic image with added brushwork.

I thought Tida Lena’s portrait of Afro-Caribbean artist Frank Bowling was a far better painting. I knew him years ago and can still feel the man in the picture. It is big and close up and the physicality of the paint is integral to its impact. Not that this always works. Vanessa Garwood’s Marcus, a naked man sprawling in a chair, heavily influenced by Lucien Freud and not for the better, is really horrid. Tina Orsolic Dalessio’s painting, The Poet – a pretty girl in a blue and gold kimono, wearing heavy silver jewellery – is academic perhaps, but because it doesn’t try so hard to show you it’s not a photograph, it achieves a much more satisfactory result. Smoke Break by Ola Sarri, a woman in trousers leaning back with a cigarette in her hand, could be a slightly racy Edwardian portrait, but at least it works. Girl with Headphones by Jane Beharrell is pretty much a photographic image, but is delicately painted. Openings by Thomas Ehretsmann in black and white is rather beautiful, but Aurelio by Iván Chacón is simply a painted photograph. A small self-portrait by Frances Borden, on the other hand, nicely drawn and cropped so that her face and shoulders fill the canvas, really is a good painting. The subject is looking thoughtfully to one side and her pensive air is entirely convincing.

I wish I could say that the rival Scottish Portrait Awards show, currently on view at the Glasgow Art Club, was miles better, but inevitably it shows the same unsatisfactory responses to the same dilemma. At least, however, it does face the challenge by including photography. At some level a portrait must be a likeness and that is photography’s great strength. How perverse then to make portrait photos without a likeness. The central figure in Jo Tennant’s Eve of Women’s Day, for instance, is blurred. In Tommy Go-Ken Wan’s Kuba, the sitter is hidden by bright light, and in Brenna Collie’s, Trapped, she is almost invisible in the dark.

There are, however, some first-class portrait photographs here. Mark Shields’ Late News Final, a news vendor looking out across his stall, for instance, is a fine picture. So too are Emanuelle Centi’s Bonnie, a girl laden with camping gear, and Stephen Bennett’s Loki with John in Aberdeen, two men sitting on the pavement in Union Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the paintings, however, there are the usual problems. Losing Our Annie, by Donald Macdonald, is a touching image of a woman with the lost look of dementia, but I had to

look very closely to be sure it wasn’t one of those awful photographs printed on canvas to look like a painting. In contrast, Grace-Payne-Kumar’s Niccolo, a man with long red hair and beard, is positively Rembrantesque. Bruce Richards’ portrait of an eight-year old boy called Bruce dressed up as a dandy adult, has the charm of good drawing and comic observation.

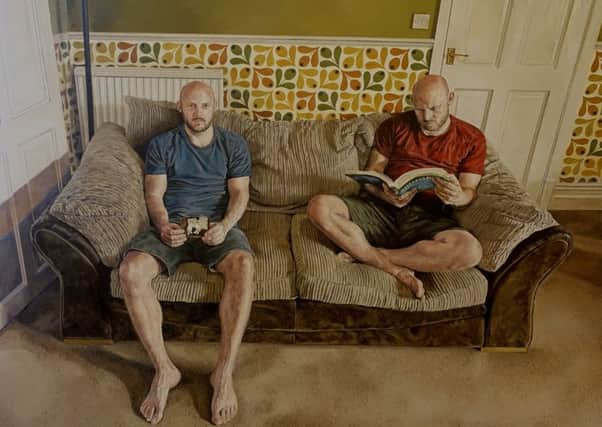

There are a lot of prizes, some for painting, some for photography. What I think was the overall first prize went to Michael Youds’ painting, I was Blue, He was Red, a double portrait of two bald men in shorts, one in a red T-shirt, the other in a blue one, sitting on a beige sofa on a beige carpet beneath a manure coloured wall. Blue T-shirt is holding a photo of two babies, likewise distinguished by red and blue. Red T-shirt is holding a Hockney catalogue, but this is no Hockney. In fact it is a rather unpleasant picture, all bald heads, bare feet and knobbly knees. The nearest feet are overlarge, too, a typical camera distortion that suggests the artist was in thrall to a photo. To my taste, first prize should have gone neither to a painting nor to a photograph, but to Maralyn Reid-Wood’s porcelain sculpture, Margaret is 17 again. Two heads conjoined, one in full colour of Margaret as she is now at 74, the other in pure glazed white as she was at 17. It is beautifully made and a tour de force on the ancient theme of time passing.

In Travel Posters at Ingleby, Marine Hugonnier also deals with photographic images, but in a highly esoteric way. She has used the internet to trace Pan AM posters from 1971, idyllic scenes of surfing and tropical forests, and then reproduced them on a large scale, recording the minute variations that appear to have taken place even as they were hidden away on some remote server. She compares this to the restoration of pictures, displaying several with conservationists’ before and after reports. The rather laboured point seems to be that images are not fixed and, if they do have a life of their own, where does the truth reside?

BP Portrait Award until 22 March; Scottish Portrait Awards until 15 February; Marine Hugonnier until 28 March