Art reviews: The Art of Intelligent Ageing | Andrew Cranston: But the Dream Had No Sound

The Art of Intelligent Ageing, The Fire Station, Edinburgh College of Art ****

Andrew Cranston: But the Dream Had No Sound, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdA new exhibition called The Art of Intelligent Ageing tells the story of how, many years later, it was realised that the results of these tests could be a goldmine of information. Researchers into ageing recognised that if the now elderly individuals who had sat the test could be traced and tested again, a then-and-now comparison of mental ability over a lifetime would be a unique opportunity to explore how our minds change with age. After a search the records were found and in 1999, in a project called the Disconnected Mind, a team led by Professor Ian Deary of Edinburgh University set out to try to contact the survivors in Lothian of the 1932 test, by then 78 or 79 years old. Five hundred and fifty were contacted. Subsequently 1,091 of those who had sat the 1947 test were also contacted. Called the Lothian Birth Cohort, since then, though sadly but inevitably in steadily decreasing numbers, they have been tested regularly, not just with the equivalent of the original intelligence test, but in a whole variety of other ways too, giving researchers a unique and rich body of information about the ageing process.

This story is told in the exhibition with documents, photographs and other material relating to the rediscovery of the original test results, the people who make up the Lothian Birth Cohort and the research in which they have cooperated. Beyond that, however, in an imaginative enlargement of the scheme, artist Fionna Carlisle has produced portraits of 12 members of the Lothian Birth Cohort together with members of the team of researchers led by Professor Deary. Twenty-two in all, the portraits were done over the last five years, though only four are from the original cohort of 1921, together with nine members of the team of researchers. In addition, Carlisle has also included a portrait of Nobel Prize winner Professor Peter Higgs, born in 1929, who was a participant in a related study on brain and cognitive ageing at University of Edinburgh.

Except for two that are simply pencil drawings without colour, the portraits are in pencil, watercolour and acrylic on paper. They are all the same size, the actual portraits about half life-size. The figures are drawn against plain paper without any background and the overall effect is informal, casual even. The elderly sitters reflect the fragility of age, but they are spirited too and the artist has caught that combination beautifully. By all accounts the likenesses are true. Occasionally a photo of the sitter as a schoolchild displayed alongside adds poignancy to the exercise. Portraiture is always social to some extent and that is what these are, a record of a social exchange between the artist and the sitters. Indeed, in the labels she has given some account of her encounters during the sittings, bits of conversation recording memories and sometimes sadly unrealised ambitions. The whole exercise is clearly invaluable and the portraits are a real addition to it. If anything could be added, it would be to record more than just these fragmentary details of the lives of this remarkable group. There is history here, but we only glimpse it.

The exhibition is in the old Fire Station on Lauriston Place, now part of Edinburgh College of Art. It is just as it was with even the fireman’s pole still in place. Still unadapted like this, it is a rather brutal environment for visual art. I hope the College won’t follow the example of Tramway and just leave it like that.

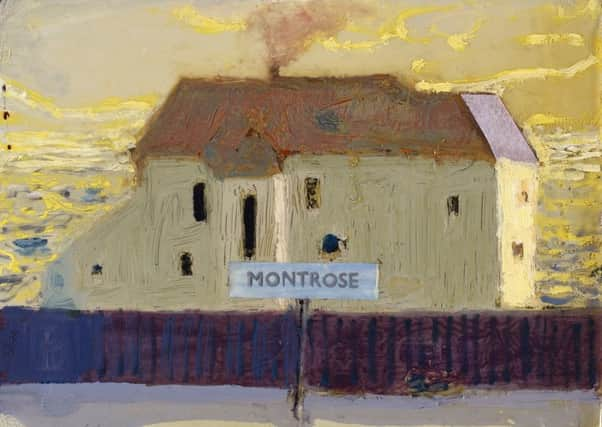

The Ingleby Gallery in the former Glasite meeting hall in Edinburgh is, in contrast, a brilliant adaptation of what at first must have seemed an unpromising space. It was a church with pews and pulpit, but is now a tall, square hall, perfectly plain and beautifully lit from an enormous central skylight. It is ideally suited to the display of paintings and the current exhibition of work by Andrew Cranston is indeed of paintings. They are tiny, however, and with an almost comical effect they make the space seem correspondingly enormous.

Long ago, Cranston seems to have hit on a way to avoid buying expensive canvasses: hardback books are bound in it, so why not paint on book-covers? That is what he does and it is also what limits the size of his work. His delightful little pictures are domestic in feeling and often in subject. They are freely handled and rich in colour. His choice of close colour harmonies and his frequent use of pattern clearly recall Vuillard and Bonnard. Indeed, he paints a nude in the bath in direct homage to Bonnard, but occasional touches of pointillism also suggest the inspiration of Seurat or Signac. A nice homage to the Post-Impressionists, his show is also a quiet but effective declaration of the continuing value of the tradition of painting that we have inherited from them. - Duncan Macmillan

The Art of Intelligent Ageing until 24 November; Andrew Cranston until 21 December