Art review: Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ****

At about the time Charles Saatchi was buying up the landmark works of BritArt, he began collecting the pictures of Paula Rego. A figurative painter approaching her sixties, Portugese but trained at the Slade, Rego had little in common with the YBAs but sharing their moment gave a well deserved boost to the career of this singular artist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow 84, Rego is being celebrated in all quarters: a major show in Paris last year, a retrospective planned for the Tate in 2021, and this touring exhibition, curated by Catherine Lampert, the former director of the Whitechapel Gallery, which (excluding an important show of prints at the Talbot Rice Gallery in 2005) brings a major body of her work to Scotland for the first time.

Lampert traces a line through Rego’s work which diverges from the established route. If Rego can be categorised at all, it is as an interpreter of stories – fairy tales, folk talks, nursery rhymes – filtering them through her own imagination and experience. This show largely sidesteps this strand, foregrounding instead the ways in which she addresses the political and moral issues around her.

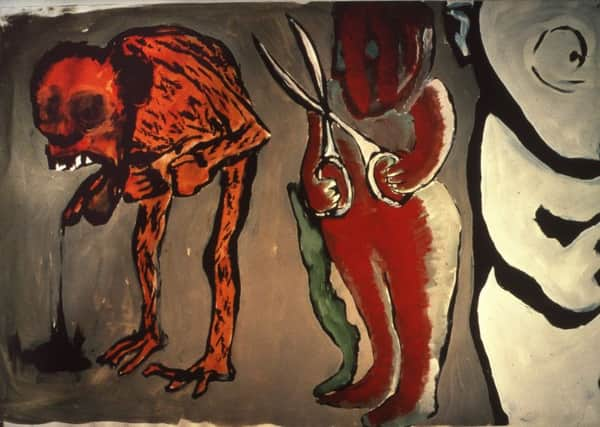

The show begins with a selection of early works made in the 1960s in Portugal and rarely shown in the UK, vigorous political paintings commenting on the repressive dictatorship of António Salazar. Stylistically, they are very different from her later work, drawing on a range of styles – abstract expressionism, pop art, surrealism, elements of high modernism – fusing them together by the sheer force of her own vision.

They are not easy pictures to decode; elements of myth and allegory come together with satire and reflections on personal experience. In all her work, Rego is rarely talking about just one thing. Her comments on the Salazar regime are intertwined with a more personal narrative about herself and her family.

The 1970s and early 1980s were dark years as Rego, back in London, nursed her artist husband Vic Willing through advancing multiple sclerosis. The two paintings from her Red Monkey series, in which she used animal avatars to explore human relationships, seem crude in comparison to her later work. These, in turn, evolved into a powerful series of paintings about girls and dogs, exploring the complex emotions of the caring relationship – loyalty, resentment, love – through the metaphor of child and animal.

From then on, she began to work on a larger scale, and in a more realist mode than before. The Maids (1987) is inspired by Jean Genet’s play of the same name, which in turn was prompted by a brutal true crime. In the picture, one maid touches the hair of a primly dressed woman at a dressing table in a gesture which might be consolation or threat, while a second maid embraces a younger woman who might be reaching for her, might be pushing her away. It is full of unease and tension, a shifting balance of power.

The show invites us to see the seismic shifts in Rego’s work happening in front of our eyes. After The Maids, she abandons acrylics and starts using pastel with increasing ambition, drawing from life and creating complex tableaux in her studio. All of a sudden, one feels she has arrived at the medium in which she is most comfortable, which best unites her incredible skills as a draughtswoman with the ideas she wants to explore. Taking Rego’s work away from the dominant fairy tale narrative, one sees that her real subject is power, how it apportioned and how it shifts, in society and in individual relationships. Her moving Dog Women series, made after Willing’s death in 1988, is an intimate exploration of love, loyalty, subservience and defiance, in which women are painted behaving like dogs, sitting obediently, and – movingly in one case – lying asleep on her lost master’s jacket, water bowl at her side.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe stories she selects, from a wide range of sources, are stories which allow her space to explore scenarios of shifting power, whether Snow White, the Portugese 19th-century classic The Crime of Father Amaro, Hogarth’s Marriage A-la-Mode or Martin McDonagh’s play The Pillowman. Her approach is always multi-faceted, big universal themes woven into a fabric of memories and allusions perhaps known only to her.

Perceptively, she observes how love and compassion are also connected with power, and she doesn’t hesitate to change a story when it suits her: The Crime of Father Amaro is the tragedy of an abused woman, but she finishes it with Angel, a glorious female avenger demanding justice for the women of the story, perhaps for all women wronged by men.

Sometimes an issue spurs her into action, such as the referendum to legalise abortion in Portugal in 1998 which failed, in part due to low turnout. In response, she made a striking series of pictures showing women forced to attend backstreet abortionists. Hard-hitting without being explicit, they focus on the women themselves, steady-eyed, determined, full of restrained emotion. She was credited for helping to shift public opinion before a second (successful) referendum in 2007. There is a similar driving concern behind her work on Female Genital Mutilation but these works have a grotesque magic realism, as if the realities of this practice are too abhorrent even for Rego to confront in a realist way.

As an artist profoundly aware of women’s experience, she also turns her gaze to the art world. In Joseph’s Dream she reverses convention, showing us a young woman painting a sleeping older man, while 2011’s Painting Him Out shows a female artist painting over a man in a complex scenario dominated by women. As ever, nothing is straightforward; beyond the obvious one, there are questions being asked here which we can only guess at. This show is not easy viewing. The focus on political and moral subjects means that we see more of Rego in serious mood, less of the satirist of social mores (as she surely is in the first two Marriage A-la-Mode paintings), or Rego having fun (as she is with Dancing Ostriches). But it is well worth spending time with all these works, allowing them to perform their gradual, layered acts of revelation (and make sure you leave time for the last room, home to a collection of drawings, prints and the superb biographical film made by Rego’s son, Nick Willing).

Rego is a revered figure for young artists pursuing a particular course, and with good reason. Here, we see her fierce and fearless engagement with the world around her, carried out with consummate skill and singular vision. Yet, there remains a point at which her work shifts from our grasp, a singularity, even defiance, which makes her a standard bearer for no one but herself. n Until 19 April 2020