Art review: A New Era, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

A New Era: Scottish Modern Art 1900-1950, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ****

If Scottish artists were really just empty vessels waiting to be filled from a foreign fountain, you wonder how such a thing could happen, but the exhibition doesn’t explore that question at all. It starts instead from a family tree of modernism drawn in the 1930s by J Alfred Barr, director of MOMA in New York. For Barr, everything sprang from one fountainhead, essentially Cézanne. The closer you were to the source, the more authentic you were. In this perspective the Scots were outsiders, but Barr’s genealogy simply adapts Vasari’s highly tendentious view of the Renaissance as a single tree that spread its branches. It has taken most of 500 years to break the constraints of Vasari’s vision. Barr’s is less compelling, but does nevertheless quite wrongly shape our thinking about the 20th century.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe true story is more complex, more fluid and more nuanced – more a wood than a single tree. Go back to Fergusson’s Étude de Rhythm, or his even more ambitious At My Studio Window from the same year. Colour gave the name colourist to Fergusson and his friend and companion in Paris, SJ Peploe. Cubist painting was almost monochrome. Fauvism was in contrast all about colour – but these paintings, although brilliant, aren’t fauve either. When you look at them, or the brilliantly coloured still-lifes that Peploe painted at the same time, you have to remember Arthur Melville, who long before Matisse was a pioneer of brilliant colour.

The colourists acknowledged Melville’s influence. No-one, however, has traced his parallel influence in Munich, home of Klee and Kandinsky, though it was acknowledged at the time. Equally, Rennie Mackintosh was a formative influence in Austria. Neither Melville nor Mackintosh is here, but instead of Alfred Barr’s simplicities perhaps this story should have been explored as it would cast light on the whole story. Fergusson and Peploe were not ingenues in Paris. Mature artists, their progressive background made them open to new ideas and that continued to be true of many of their successors in Scotland.

That is certainly not to deny the power of the continental example, however. In 1913, for instance, Stanley Cursiter painted three striking futurist works. His willingness to try this new fragmented style and the skill with which he deployed it suggest a similar open-mindedness, but Cursiter seems to have been driven more by fashionable curiosity than by conviction. In the same year, the Edinburgh College of Art Student Revel was on a futurist theme, for instance. However, Cursiter may also have been discouraged by the uphill task he would have faced. The year before, Peploe had come back from Paris with paintings that were mildly touched by the cubist muse, but his dealer in Edinburgh refused to show them. Rather poignantly, Duncan Grant’s painting The White Jug reveals the same pressures. Painted in 1914, it was one of the most abstract paintings by any contemporary – at least, it was until 1918 when Grant introduced a still-life to make it more acceptable.

The conservatism that checked Cursiter and Grant reflected insecurity. These 50 years were difficult for Scotland. The economic tide was already going out and the 1920s and 1930s were lean years. Even so, the distinctive, radical Scottish light may have flickered, but it was not put out. The bleak power of William McCance’s drawing of a gigantic head, like some fierce god from an unknown mechanistic civilisation, is really only paralleled in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Others, too, absorbed new ideas and worked them into something fresh. Beatrice Huntington’s Spanish Muleteer is an austere reading of cubism. In his still life The Blue Fan, her friend, colourist FCB Cadell, created a brilliant, flat pictorial harmony which has absorbed any such influence and turned it into something wholly original. Meanwhile, Cecile Walton’s lovely Reverie is a poetic riff on Delaunay and orphism.

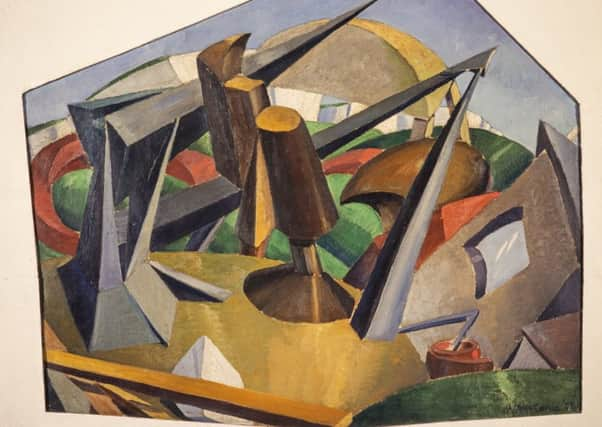

Towards the end of the First World War, Fergusson painted a series of very sophisticated dockyard pictures. It is shame, however, that none of his Highland landscapes painted a few years after the war are here. They brought modernism to Scotland, not as an exotic import, but as a way of seeing our own place. They may have helped inspire William Crozier’s famous cubist painting of Edinburgh Castle and certainly fired William Johnstone’s ambition. This is seen in its maturity in his great painting A Point in Time. It is a monument of the Scottish Renaissance, a fierce reaction to scared conservatism led by his friend Hugh MacDiarmid. Significantly, Johnstone was inspired by contemporary American painting as much as by the surrealism which he encountered as a student in Paris.

Lively curiosity about new ideas meant that there was a steady flow of avant-garde art to Scotland. After a show of Paul Klee’s work at the SSA in 1934, for instance, his inspiration is reflected in adventurous works like Gillies’s Edinburgh Abstract and Maxwell’s Harbour with Three Boats. Surrealist paintings shown here also found a lively response. Edward Baird’s Distressed Area, apparently just a painting of an abandoned shed on an Island near Montrose, is a genuine surrealist masterpiece. William Crosbie’s La Vie Distraite is also ambitious if less convincing. In The Evening Star, however, James Cowie’s metaphysical vision, if touched by surrealist ideas, seems nevertheless to be quite his own.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe sculpture is one of the joys of this show. Norman Forrest and Tom Whalen both made beautiful work in wood and in stone that elegantly blends the inspiration of Brancusi, the primitive and the Romanesque.

During the Second World War and in the post-war years, Scottish art gathered speed again. Immigrant artists Josef Hermann and Jankel Adler joined forces in Glasgow with JD Fergusson to produce a small modernist renaissance. The Two Roberts – Colquhoun and McBryde – were its principal disciples, but it is a shame that there is nothing of the work of the less well-known New Scottish Group artists, though the show does otherwise bring out artists who have been forgotten like Tom Pow and Benjamin Creme. Jock Macdonald’s vivid automatic drawings are a revelation, too.

Advertisement

Hide AdPost-war it was the Scots who led the way back to Europe. William Gear, William Turnbull, Alan Davie and Eduardo Paolozzi really were the pioneers for Britain as a whole of an explosive new expressionist art. William Gear’s dramatic Autumn Landscape created a scandal in 1950 when it was purchased with public money. Alan Davie’s Saint and his Jingling Space likewise speak with a powerful and independent voice of the difficult birth of a new world order.

It is a shame therefore that Paolozzi and Turnbull are not so well represented. One of Paolozzi’s formidable drawings, or one of his bigger early sculptures would have been a fitting finale for the show. He was above all a radical, European Scot and could personify this whole remarkable story. It is however a rich and fascinating show.

Until 10 June