Art: Forster | Gouldson | Leith School of Art

Richard Forster: Modern

Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh

Star rating: * * * *

Leith School Of Art Alumni Exhibition

Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh

Star rating: * * * *

Rebecca Gouldson: Industrial Shift

Edinburgh Printmakers

Star rating: * * *

Drawing has been among the principal instruments through which, over the last few centuries, we have explored the workings of the world and applied the understanding that has given us. Before photography it was the only means of visual investigation and record and it still is superior in many ways. It was no accident that two of the finest British draughtsmen, Allan Ramsay and David Wilkie, were prominent figures in the Scottish Enlightenment. Drawing was an integral part of the common pursuit of better understanding of the world and the people in it that drove that movement. Drawing is no longer a core study at art schools. Now it is just one choice among many and, as it needs time and patience to learn to draw, it has inevitably ceased to have a central place in contemporary art. Richard Forster is an artist who does draw, however. He has always done so. He began as an artist drawing privately in his bedroom. His habit remained private, too. “For a long time,’ he said, ‘to be public with my drawings seemed quite a fruitless exercise.”

In other words, fashion couldn’t cope with it. What was a private practice has now become a public one, however. He has returned to his point of origin, but this shift also coincided with an actual return to his roots. Born and brought up in Yorkshire, he worked in London with some success during the YBA decade, but then turned his back on the Metropolis to return to Yorkshire and concentrate on drawing.

Advertisement

Hide AdForster’s show at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh consists of very careful drawings from photographs. But isn’t that a dead-end? What can drawing do that the photographs have not already done? Forster is one of a number of artists currently rediscovering drawing for whom it is precisely the difference from photography, even when photography itself is the subject, that is so fascinating. A drawing from a photograph is an act of comprehension and absorption. It both takes possession of what is in the photograph and shares it and in that sharing Forster’s subject matter is critically important. One work, for instance, consists of a series of drawings of photographs of an anonymous industrial landscape taken on successive days from a moving train. With them there is also an abstract, three-dimensional model, made of wood, but coated in gesso with the original woodgrain obsessively recreated in pencil. The whole work is called A Rehearsed Inability to Know This (Un)Place. Ten seconds of a train journey from Saltburn. The model seems to be an abstract rendering of buildings seen fleetingly in the drawings, but extended horizontally as though by the movement of the artist’s viewpoint. It is almost a Futurist conceit. The woodgraining is obsessive, but this is true of all these works. It is something that artists seem frequently to fall into as they rediscover drawing, as though it is the action itself that matters rather than the thing drawn. It is intensely introspective, like so much contemporary art. Though too often it is merely self-indulgence along the lines of “Look at me! Aren’t I interesting?” introspection can be a route to shared illumination. It certainly is with Forster.

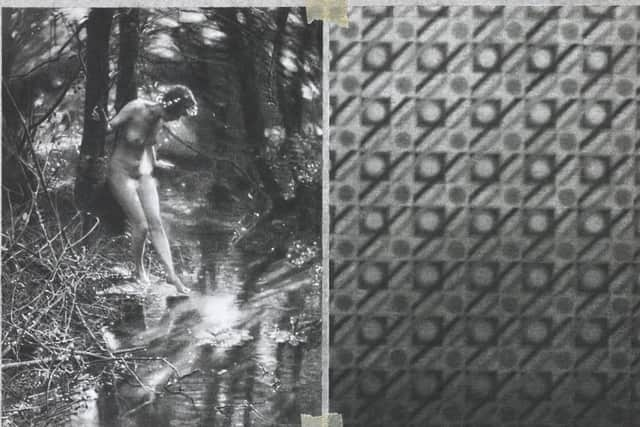

One striking feature is his preoccupation with time: time passing, time expended on his drawing, but also time as history. Being from Yorkshire, Forster was a witness to the Miners’ Strike and the whole political assault on heavy industry and organised labour of which it was only the most dramatic manifestation. The consequence was the collapse of industry. Returning home from the frothy metropolis was a way for Forster to confront this. It is there in the explicit transience of the industrial scenery seen from a passing train, but he also takes another angle on it in other works here, though transience is explicit in them too. One sequence of 24 drawings, for instance, is of snapshots taken from an archival film that he saw at the Bauhaus of the building of the Torten Estate at Dessau in 1926-28. An idealistic project by the leader of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, this estate was intended to provide affordable housing (how topical that sounds). But Forster’s format again suggests transience, the transience of history, but also of ideals. The Bauhaus features again in his American Pastorals, a series of odd, two-part pictures pairing a 1920s “art” photograph of a naked girl in a Garden of Eden landscape with a piece of Bauhaus design. (The two parts are apparently joined with masking tape but it is painted tromp l’oeil.) It is as though both parts of the image were equally unattainable, the fantasy nude and the idealism implicit in the abstract design.

Echoes of this same sense of failed idealism permeate several pictures of East Germany inspired by “Ostalgie”, a half-ironic nostalgia for the former Communist state, as though for all its faults, like the nudes in the Garden of Eden landscapes, there had been a kind of innocence about it and so the Fall of the Berllin Wall was like the Fall itself and also a loss of innocence.

That in turn suggests an interesting analogy with the Miners’ Strike and the consequence of the policies against which it was a heroic, but doomed, resistance. For all that, however, the outstanding works in Forster’s show are three six-foot high drawings of the sea where little waves draw scalloped lines at the water’s edge. These have neither politics nor history and are simply beautiful.

Forster’s interest in decayed ideals finds an echo in the work of Toby Paterson, whose exploration of the Utopian Modernist architecture on both sides of the Iron Curtain and the shortfall between ideal and realisation has been one of the most distinctive and worthwhile recent contributions to Scottish art. Paterson is also one of the star alumni of Leith School of Art in an exhibition at Dovecot marking the school’s Silver Jubilee. Leith School of Art was started by Mark and Lotte Cheverton in 1988. Tragically, the founders were killed in a car accident in 1991, but the school has flourished in spite of that loss. There are now some 300 students enrolled. In the introduction to the exhibition catalogue Alastair Salvesen writes that the founding ethos was “to establish a positive tradition for teaching art which is ongoing”. In other words it is a place where drawing matters.

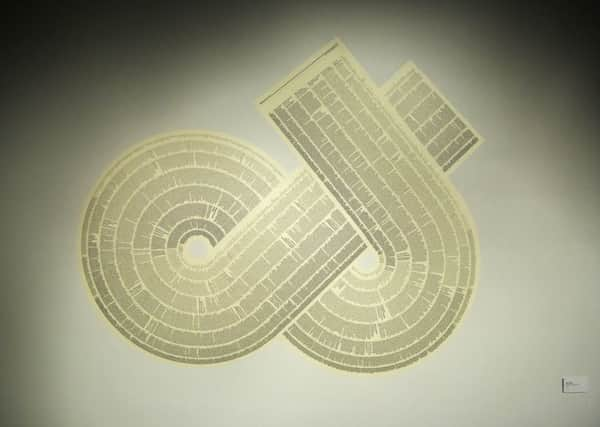

The diversity of the present show, however, suggests that though the principles may be conservative, the results are not. Seventeen artists are represented. Their work ranges from Paterson’s essays on the aesthetics of idealist architecture, through Tim Moore’s exploration of a rather similar aesthetic in graphic design and Tommy Grace’s abstract typography, to films by Jamie Stone and fabrics by Jane Keith. Believe it or not, in paintings by Alastair John Gordon there is also more tromp l’oeil masking tape and carefully rendered wood grain, the latter painted this time, not drawn.

Advertisement

Hide AdRichard Forster’s implicit theme of industrial dereliction is also echoed in Industrial Shift by Rebecca Gouldson at Edinburgh Printmakers. The imagery she uses is principally derived from photographs of abandoned machinery and industrial sites. She then etches these onto industrial materials like copper, bronze or steel in highly polished discs or composite shapes. The results are very beautiful, but unlike Forster’s fleeting images made permanent by the effort of his drawing, these have the gloss of precious objects. No ripple of turbulent history ruffles their shiny surfaces.

They are sincere art works, but their gloss and their imagery of industry made safe make them perfect vehicles for the expression of corporate self-esteem. It is no surprise to learn that they have been placed in banks, investment companies and yachts.

Richard Forster until 21 June; Leith School of Art until 31 May; Rebecca Gouldson until 24 May