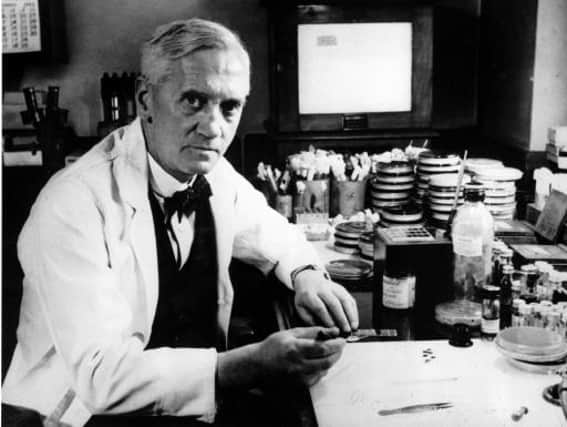

Alexander Fleming: Everyman who saved millions

Consider how many lives Alexander Fleming has saved with the discovery of penicillin. Most people return from a vacation to a stack of mail; Fleming returned to a universal miracle cure for infection.Lady Luck can take credit for the Penicillium Notatum mould growing in a sidelined petri dish, but the Scottish bacteriologist would have been more than a footnote in medical history with or without his observations that day.

Born on 6th August 1881, Alexander Fleming grew up on a Scottish hill farm and spent much of his youth observing the natural world and recording his findings - a scientific dictum he would adhere to all his working life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt 14, he moved to London to complete his education. A legacy left to thim by his uncle allowed him to pursue a career in medicine. He chose St Mary’s Medical School after experiencing the water polo team's admirable sportsmanship first-hand.

He had hoped to qualify as a surgeon but at the turn of the century he accepted a post in the exciting new field of bacteriology. During WW1, Fleming worked as a ranking army medic from a military hospital lab set up in a French casino in Boulogne. Here he became an expert on the bacteriology of wound infection.

He also contributed a logistical theory of the enzyme lysozyme, present in many bodily fluids with a mild antiseptic effect, significantly advancing developments in sterilising surface wounds. It did little to heal the horrors of war, but the discovery later drove him to pursue the therapeutic properties of penicillin.

Returning from a holiday on 9th September 1928 he discovered Penicillium Notatum mould growing wild in a petri dish and destroying all the bacteria in its path. He moved to isolate the antibiotic agent and the rest is history.

Renowned historian Kevin Brown holds the honour of being Trust Archivist and Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum Curator at a reconstructed lab in the very room Fleming made his world-changing discovery.

Fleming accepts his Nobel prize in 1945

“We’ve tried to show what it would have been like back in 1928, but the laboratory didn’t stay intact for all of these years,” he says.

“Fleming moved out of there in the 1930s and it was used by medical midwifery students. Fleming’s own son slept here as a medical student in the 1940s. It wasn’t until the 1990s when it was turned back into a museum.”

Eight months later, Fleming presented his research to the scientific community in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, but it turned few heads. Fleming was a lone researcher and knew his limitations. Unable to proceed further with his research, Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain stepped in to lead a team synthesising penicillin and passed clinical trials between 1939 and 1941.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFleming, Florey and Chain all accepted the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 for the discovery and development of rudimentary antibiotics.

Kevin explains that the race for penicillin production was a key development contributing to the allied victory in World War 2.

“The effect of the war was to almost hold them back at first because they were having to deal with shortages and needing to improvise,” he says.

“From 1941 they were able to bring penicillin into some limited use and labs at the William Dunn School of Pathology at Oxford were, for a time, the biggest penicillin production unit in the United Kingdom, perhaps in the world.”

“Having a way to fight infection gave you a sizeable military advantage - you could get your men back into action more quickly than your enemies. In America, that was a big impetus to the development of modern production methods of penicillin.”

Nazi Germany had taken penicillin research down an altogether different path. With most of their best scientists in exile, imprisoned in camps or deceased, the Reich had to rely on synthetic production.

A 3D model of the Benzylpenicillin molecule

“Germany had a history of achievement in the chemical industry so they were putting a lot of emphasis on synthetic drugs and before 1945 it was widely thought that it would be easy to synthesise penicillin,” explains the historian.

“Only once the chemical structure was understood did they realise that it wouldn’t be so easy and would be too expensive.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If you have the faith in being able to synthesise something and think you’ve got a great tradition in chemistry then you’re more likely to place the emphasis on developing synthetic penicillin. Great Britain and America also put great effort into trying to synthesise it, but they were also putting effort into producing it from the mould at the same time.”

As importance as the discovery of penicillin, Fleming’s contribution in making medical science acceptable to the Leyman was a refreshing change of pace. He was a man who seemed to be ordinary, just like everybody else, who’d been involved in a lifesaving medical breakthrough that would save lives in a time when science was becoming something to fear after a long shadow was cast in the wake of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Penicillin saved many lives in the war and it was associated with an unassuming, everyman.

As a national figure, Fleming’s ashes are buried in St Paul’s behind an bespoke marble plaque sourced from the same quarry as Athens’ Parthenon.

Etched into the plaque, a thistle is carved alongside the Fleur-de-lys of St Mary’s Hospital London, memorialising the Scottish roots he embraced and his institutional loyalty over 54 years.