1960s egalitarianism that helped produce the Rolling Stones has been lost as UK politics has turned into an empty right-wing charade – Joyce McMillan

Yet it is true that in some ways, to be young in the 1960s and 70s was a rare privilege. University education was free throughout the UK, rents were cheap, summer jobs were easy to find, even the dole was lightly policed by today’s standards; and as for the music – well, its continuing massive popularity speaks for itself.

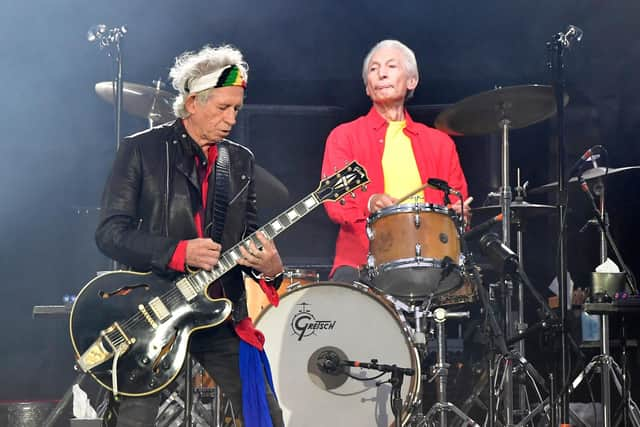

So it’s perhaps not surprising that when the death was announced, this week, of the Rolling Stones’ drummer Charlie Watts, there was a huge outpouring of grief and nostalgia among rock fans of a certain age.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike his band mates, Watts was a war baby, born in London in 1941. His dad was a lorry driver, and he spent his early years in a prefab in Wembley. After school, he went to Harrow Art School, although music was always his first love, and worked as a graphic designer. He also played in various bands around the London rhythm and blues scene; and in 1963, he joined the Rolling Stones, providing a steady and brilliant backbeat to their inimitable brand of rebellious, sex-charged rock, for the next 58 years.

All of which raises some questions, as we mark the end of that era, about the kind of world into which Charlie Watts and the Stones emerged, in the 1960s, and how it differs from the social and cultural scene of our time.

I’m not about to idealise 1960s Britain. For most people, it was a country in which hard manual labour was still the norm for men, and a searing lack of equal rights and respect the norm for women. Homophobia and racism were rife; and the young people who emerged into higher education during that decade certainly had plenty to rebel against.

What the country did have, though, was a vibrant national political scene which fully captured many of these tensions, and allowed ample room for debate about Britain’s future.

When Harold Wilson was elected Labour Prime Minister in 1964, he presented himself – very credibly – as the voice of the future rather than the past. The Labour Party at that time arguably represented a critical alliance of ordinary workers, rebellious young people, committed socialists, and progressive social thinkers, all opposed to the world of Tory privilege and double standards exposed during the Profumo affair of 1963.

The party itself was a notably broad church; but its strong links to the trade union movement – not only financial, but also involving a huge and constant interchange of people and ideas – acted as both ballast and power-base, ensuring that social change moved at a pace working people could support, and that the party never lost sight of its basic raison d’etre, which was to take the voice of ordinary working people into parliament, and to keep shifting the balance of power and wealth in their favour, by every peaceful means possible.

It’s therefore well worth considering what we have lost, since the 1960s, in terms of the radical vigour of the political debate that helped create and sustain the country in which five working or lower-middle-class boys from the London suburbs could become the second most famous band in the world, and four kids of similar backgrounds from Liverpool the most famous of all.

Today, while a thousand radical flowers bloom in the backwaters of the internet, the range of political debate taken seriously in mainstream media seems much narrower than in the 1960s, with even moderately radical documents like Labour’s 2019 “green new deal” election manifesto somehow dismissed as absurd or unthinkable.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis week, the former Labour MP John Woodcock, now Baron Walney and an adviser to the UK government, was reported, almost comically, as telling Extinction Rebellion activists that while he felt it was wrong to class them all as potential terrorists, it would nonetheless be a serious matter if they were found to be concealing “anti-capitalists” in their ranks.

And five years after a solid 16 million British citizens voted not to leave the European Union at all, it now seems to be considered impolite, in some quarters, even fully to debate the negative consequences of Brexit, when they are staring us in the face.

It’s possible, of course, to make extensive lists of the reasons for this relative timidity in 21st-century British mainstream politics. The dominance of strident right-wing voices in the popular print media, the long-term decline in BBC independence and boldness, and perhaps above all the Labour Party’s desperate and eventually self-destructive attempts to embrace middle-class values and distance itself from the trade unions, while hanging onto their cash; all of these have played a part.

The result, though – even as parties make ever more successful attempts to look more diverse in terms of race and gender – has been a loss of ideological, intellectual and class diversity, and of robust debate about the real redistribution of power, that has contributed to the bland managerialism and nit-picking pettiness of much contemporary party politics, alienating millions of voters. And that alienation has led, in turn, both to the sense of anger and exclusion that fuelled the Brexit vote, and to growing movements in Scotland and Wales to leave behind what now seems the empty right-wing charade of British politics, and to reach for a more meaningful political life in a reborn smaller nation.

Can’t get no satisfaction, in other words, from the kind of fearful, narrow and conservative-minded politics now available at UK level, as exemplified by Keir Starmer’s Labour Party; and it’s hardly surprising that many UK citizens who care about politics and its power to change lives are now – with a quiet nod to the rebel spirit of the Rolling Stones, and their great rock contemporaries – beginning to look for that satisfaction elsewhere.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.