Why an independent Scotland in EU might not be paradise – Bill Jamieson

It is time we lifted up our downcast, troubled eyes to a world beyond Brexit. Yes, for such a world exists, however obscure it may now seem. Look beyond the dire consequences if we left the EU and instead to a horizon that’s barely discussed at present: what would the world we like if we opted to Remain?

It could well come to pass: in the Grand Guddle that awaits us this autumn – mayhem in parliament, a new Prime Minister struggling to gain credibility, a plan for a fudged but still traumatic Brexit exit is put to the electorate. It is carried by a small majority.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut there is uproar in Scotland. A deafening clamour arises for a second independence referendum. A ‘Yes’ vote results and an exultant SNP administration launches the process for Scotland to be admitted as a tall, proud, independent member of the EU.

We revel in a turbo-charged internationalism, our destiny inextricably bound to a union of outward-looking liberal democracies. Euphoria would barely begin to describe it as the Saltire is raised to flutter proudly alongside the flags of European nations outside the European Commission.

We take our place in the highest councils of Europe with enhanced office and legations. Chauffeured limousines disgorge a new cadre of senior Scottish government officials. Our leading institutions, government agencies, business organisations, universities, farming and fishing industries, oil and energy operations, are charged with new purpose and challenge. What’s not to like?

It is in the nature of euphoria to settle down. The charisma of change gives way to routinisation, a ‘new normal’ cemented by fresh relationships, structures and bureaucracy. But before long we come to an under-appreciated feature of the EU. It is no static monolith. For its defining purpose is to advance, expand, move forward. Its steady state requires momentum.

It has already travelled through the Maastricht Treaty (1992) and the Treaty of Rome (1957). The latest is the Treaty of Lisbon that amends the two treaties which form the constitutional basis of the EU. It was signed in 2007 and came into force in 2009. Its stated aim is to “complete the process started by the Treaty of Amsterdam (1998) and by the Treaty of Nice (2001) with a view to “enhancing the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union and to improving the coherence of its action”.

Prominent changes include the move from unanimity to qualified majority voting in at least 45 policy areas in the Council of Ministers (due to take effect next year), a more powerful European Parliament, a consolidated legal personality for the EU and the creation of a long-term President of the European Council and A High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. Such is the direction of travel.

And Scotland may be content to go along – for a while. How long might it be before Scotland, as with many other EU countries, spawns a populist Eurosceptic movement of its own?

Inconceivable? More than a million Scots voted to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum. And many would be uncomfortable with an increase in the powers of the EU over Scottish affairs. Fishing, for example, is regarded as a vital part of Scotland’s coastal economy and heritage. And there is a widespread concern that the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy has been bad for our fishing industry. So control of farming and fisheries could well become flashpoints in an EU-member Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow some have voiced unwarranted fears over EU tax policy. There is no immediate change. But the Commission has recently suggested rolling out Qualified Majority Voting to different sections of EU tax policy gradually, using a passerelle clause (this allows the alteration of a legislative procedure without a formal amendment of the treaties) in four stages.

The first would see QMV introduced for measures which focus on addressing tax fraud, evasion and avoidance, and facilitating compliance. The second would see rules introduced for tax policy measures that aim to achieve public policy objectives in areas like the environment, public health or transport. The third stage would see the national veto relinquished for EU measures in the field of indirect taxation (VAT and excise). Finally, QMV would be applied to all remaining EU tax policy measures, “including areas such as the Common Corporate Tax Base, Financial Transaction Tax and taxation of the digital economy”.

All this could be dismissed as a speculative ambition as no immediate changes are envisaged. But it highlights the general direction of travel and the thorny issues that a progressive EU-member Scotland would have to face.

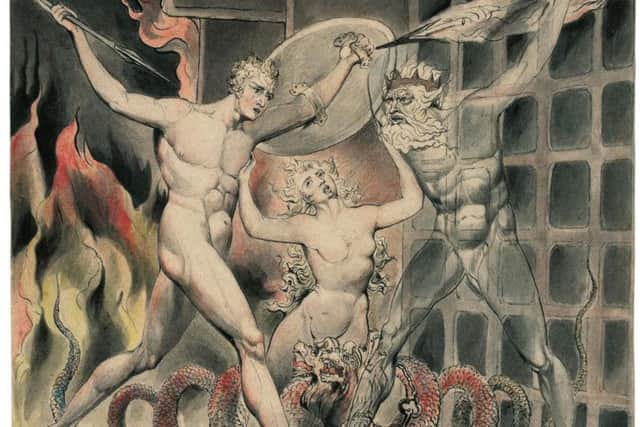

Arguably more immediate and pressing issues would be whether Scotland would be required to commit to membership of the Euro or able to maintain a separate currency and independent central bank: loss of these would be met with considerable misgivings among SNP supporters – as would European Commission oversight of debt and deficit levels. For many, EU Paradise gained may morph in time to Paradise Lost – and the tolling bell of ‘independence’ would acquire an altogether different ring.