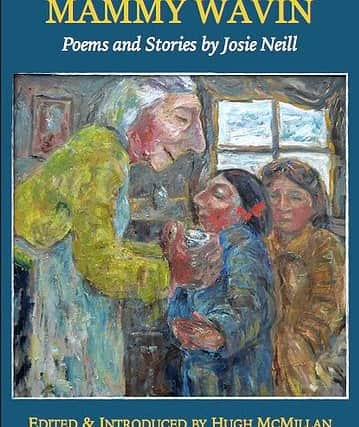

Book review: There’s Ma Mammy Wavin’, by Josie Neill

Though Dumfries writer Josie Neill is celebrating the publication of her first poetry collection at the age of 86, it is the product of a long writing career. She has been anthologised, and was one of the readers at the 70th birthday celebration of Galloway poet Willie Neill (no relation) alongside Norman MacCaig and Iain Crichton Smith. Hugh McMillan at Drunk Muse Press has worked with her to recover these poems from drawers, old audio recordings and from her memory, believing her to be an important voice in Scottish writing, particularly in the Scots language.

Although Neill spent much of her life in Dumfries, where she was a teacher, she grew up in the Ayrshire mining village of Muirkirk. Many of her poems evoke that: sky which “flaps in battered banners”, miners coming home from the pit, “their dazzing teeth, their swagger, sturdy limbs”. This is less nostalgia than a deep mining of the past, fixing it to the page in vivid nuggets of memory.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt is often winter in these poems, a season of danger as well as magic; the title of the book comes from a poem in which the young poet makes a perilous journey home through wintry fields. Home is a place of safety, the bright doorway towards which she struggles through the blizzard, a place of hearth and family, songs and stories.

She has, she says, “a parted tongue”, writing both in Scots and English, and employing them separately (“Fuse them, never! / I’d choose to be a fork-tongued creature / Than a spirit diminished.”) Her Scots poems are written in a warm, rolling Ayrshire Scots, alive with words we hear little these days: “wanchancy”, “furritsome”, “grunzie”.

At their best, these poems have a natural flow in which meaning is laid down in harmony with music. Some also recall an older ballad tradition: the bogle in the churchyard, the young mother and child who take shelter at the fire one Christmas night and vanish before morning leaving no footprints in the snow.

Her work in English is perhaps less intimate, the work of a woman who has, by necessity, moved away from her roots, studied and travelled. But, at their best, the poems are no less assured in imagery or musicality. The earth at the Somme is “wrinkled and slinking / like filthy bedclothes”; sheep on the Yorkshire hills are “like weathered pegs / Pinning the air to earth”.

But it is the Scots, particularly, which stands out, a voice which seems to belong more to the world of MacDiarmid and the makars than to contemporary writing in Scots, rich and varied as it is. Neill inhabits it naturally, yet realises, poignantly, that this language – like Muirkirk and its way of life – is vanishing.

In “I Feel My Words Smoothing”, she describes the way the rough music of that Scots is fading. Yet, it comes back to her in big rocks of words – “breingin”, “skraik” – which she builds into a metaphorical cairn. “If I can get my language back, / My once-bright courage, / I’m half way home.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThere’s Ma Mammy Wavin’, by Josie Neill, Drunk Muse Press, £10

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions