New Covid drugs: How genetic research is uncovering an entirely new way to save lives from the Covid virus and other infections – Professor Eleanor Riley

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

Some people became extremely ill; many of these people died. Others had mild infections, frequently with trivial symptoms or no symptoms at all.

In the initial waves of the pandemic, socioeconomic factors – your occupation, where you lived, how many people shared your home – played a large part in whether you became infected.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnce infected, characteristics such as your age, whether you have underlying lung or heart disease, a blood clotting disorder, or diabetes, and whether or not you are overweight, plays a huge role in how sick you became.

Covid-19 risk also differs by ethnicity. Although much of this variation can be accounted for by socioeconomic and health differences, the pandemic has exposed the extent to which inequalities in health are underpinned by social and economic inequality.

However, there were also many deaths of people who didn’t fit these risk profiles: young, fit and otherwise perfectly healthy people who nevertheless became seriously ill and died.

Whilst uncommon overall, the sheer size of the epidemic meant that these “outliers” soon started to mount up. It was becoming very obvious that there were other risk factors for severe Covid-19.

Since the sequencing of the first complete human genome over 20 years ago, the UK has been at the forefront of research using small variations, mutations, in our genetic code to understand what goes wrong – at the molecular and cellular level – in people with myriad different diseases.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) attempt to link the presence of mutations in particular genes with increased, or decreased, risk of developing particular illnesses.

“High-risk” mutations can be quite rare and the change in risk associated with any individual mutations can be quite small. In the case of Covid-19, not everyone with a “high-risk” mutation will actually catch Sars-CoV-2 and some of those that do may have mutations elsewhere in their genome that off-sets that risk.

Studies also need to be able to adjust, statistically, for demographic, socioeconomic and health factors that modify the risk. So, GWAS studies need to enrol very large numbers of patients and compare them with equally large numbers of “controls”, people without the disease, from the same communities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a recently published GWAS, led by a team from Edinburgh University, DNA sequences of 7,491 Covid-19 intensive care patients across the UK were compared with archived sequences of almost 50,000 people who had participated in the nationwide health study, UK BioBank, or who had submitted samples to databases such as AncestryDNA or 23andMe and given permission for their genetic data to be used for medical research.

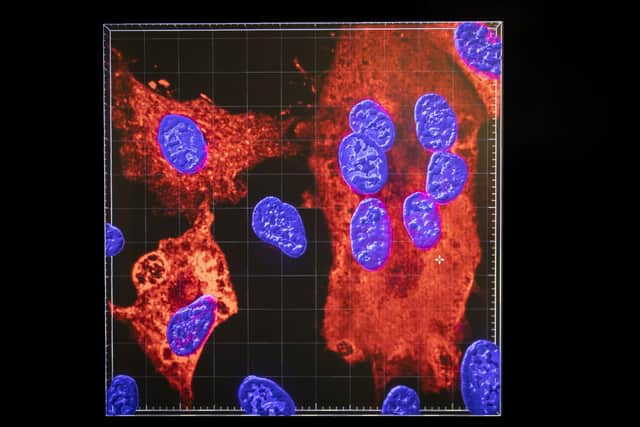

The study uncovered associations between severity of Covid-19 and mutations in genes encoding components of the immune system, inflammation, coagulation and mucus secretion.

This confirms the clinical picture that severe Covid-19 is caused by immune-mediated, inflammatory lung injury and abnormal blood clotting. Crucially, the study identifies specific molecules, encoded by these genes, that are likely targets for entirely new classes of drugs to combat virus-induced inflammation and blood clotting.

Such drugs would add to our growing armoury of therapies for Covid-19 and, quite possibly, other severe respiratory viral diseases.

Eleanor Riley is professor of infectious disease immunology at the University of Edinburgh

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.