Book review: Dark Corners by Ruth Rendell

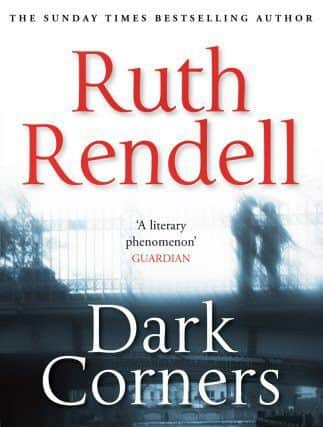

Dark Corners

By Ruth Rendell

Hutchinson, 279pp, £18.99

Dark Corners is, sadly, Ruth Rendell’s last novel. Writing both under her own name and as Barbara Vine, she was astonishingly prolific, maintaining a high standard for half a century. Some prefer her straight detective fiction – the Wexford novels – others her psychological thrillers. The latter are mostly set in London; the dark corners of the title of this last novel are in both London itself and her characters’ minds. Obsession is a recurrent subject, and, though her manner was usually laconic, she wrote with sympathy and deep understanding of even the most troubled and criminal of her characters.

This last novel begins in apparently perfunctory and scrappy style; there is little of the dark atmospheric writing of her most powerful books. Not everything hangs together. There is one remarkable unexplained episode. The absence of explanation is, I think, deliberate. There are gaps in the fiction, just as there are in life. Not everything reaches a conclusion.

Advertisement

Hide AdCarl is a young writer who has inherited a desirable mews house in Maida Vale. To support him while he tries to write his second novel, he lets the upper floor to a tenant called Dermot, who works as a receptionist at a pet clinic. For many years Carl’s late father collected “samples of alternative medicines, homeopathic remedies and herbal pills”, most of which he never used “because he was afraid of them”. Carl inherits them too. He has a friend called Stacey, an actress who is worried about getting fat. So Carl sells her some of his father’s pills, supposed to reduce weight. Selling rather than giving is a bit mean, and the transaction is overheard by the dreary but oddly sinister Dermot. The pills are not illegal, but they can be dangerous and, when Stacey dies, Dermot stops paying rent and in effect blackmails Carl by threatening to take the story to the newspapers. This sets off a chain of events which the reader may suspect will lead to Carl’s moral disintegration.

A sub-plot concerns Lizzie, a friend of both Carl and Stacey. She is a petty thief, a parasite, a liar and fantasist, a nasty little girl who supplies some comic relief. She is a character-type common in Rendell’s novels, and I would think Rendell, so adept in portraying people who are not so much immoral as amoral, took great pleasure in writing her. Nevertheless she is a distraction or red herring, at least until the last chapter of the book. Even then there is no real purpose in what she does beyond a desire to make an impression.

Rendell, like Simenon, that other masterly explorer of obsession, is fascinated by the way in which apparently ordinary and uninteresting men and women can be brought to the point at which they step out of the light into darkness, brought by what seems to them to be an inexorable logic or compulsion to cross the barrier that separates the law-abiding from the criminal. It is often a slow process, but as the proverb has it, it is only the first step which counts. In giving Stacey these pills, Carl has intended to do no harm. He has even meant well. Accepting money for something for which he has no use himself, and which he has often thought of throwing away, is not very likeable. But the act itself is at worst careless. Nevertheless, it puts him on a dangerous path. The desire to retain her love and esteem makes him dishonest. He can’t face the prospect of the exposure with which Dermot threatens him. He must retain the respect of the world. Like Simenon again, Rendell recognised how the need for the respect of lovers, family, friends and the world may engender crime. Carl, being weak, fundamentally honest and well-meaning, will be a victim of character and circumstance, while the silly and mendacious Lizzie will float free.

Dermot, the pious, church-going blackmailer, is one of Rendell’s best characters, a creepy fellow, with more than a touch of Dickens’s Uriah Heep about him. Rendell, in her loving exploration of human grotesquery and the hidden places of London – what goes on behind the façades of houses – was always a Dickensian novelist. Dermot, with a platitude for every occasion, seems at first boringly ordinary, if tiresomely intrusive, only gradually to be revealed as sinister.

The opening chapters of this novel are apparently casual. You may even think they are dull, evidence of a writer whose spark has dimmed. It all seems so ordinary, so trivial. Why should you care about these commonplace people? But you soon realise that Rendell hadn’t lost her touch, that she still knew just what she was doing. Their ordinariness is the point. They may be mean or stupid or timid, but it is opportunity or the pressure of events that leads them into criminal behaviour – meanness in Dermot’s, stupidity in Lizzie’s (though her crimes are minor and would scarcely attract the attention of the law), timidity in Carl’s. One of Rendell’s great gifts was her ability to identify and reveal people’s susceptibility to temptation. I don’t suppose Dark Corners is one of her best novels; there are times when her prose and the narrative slacken. But it is still pretty good.