Art reviews: Alasdair Gray | Thomas Joshua Cooper

The Alasdair Gray Season: A Life In Prints And Posters Glasgow Print Studio

Star rating; * * * *

Thomas Joshua Cooper: Scattered Waters: Sources, Streams, Rivers

Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh

Star rating: * * * * *

Advertisement

Hide AdIn four books, Alasdair Gray’s Lanark shifts between the dystopian world of Unthank and a more recognisable, though hardly flattering, account of Glasgow as it was experienced by Duncan Thaw, a native of the city and a student at the school of art. Thaw is a thinly veiled portrait of the author who also trained at Glasgow School of Art and was an artist before he became a novelist. He has since flourished as both, although generally we are programmed to think of artists and novelists as “either-or”. Too much joined-up thinking might be dangerous, perhaps. Divide and rule is the unspoken maxim that dictates the patterns of academic thought. Gray’s work is a magnificent challenge to such diminishing conformity. His often radical moral vision has much in common with Blake, but like Blake he is put in two exclusive academic boxes and so is not seen in the round.

At the end of December it will be Gray’s 80th birthday and to mark the event, Glasgow Print Studio has put on an exhibition of his work on paper. He has had a long relationship with the print studio. Indeed, one of his very first published works, The Comedy of the White Dog, was published by the Print Studio Press, a literary offshoot of the studio. In the exhibition there is a small group of portrait drawings and another of posters. These latter are mostly for the theatre, but also include the artist’s vivid Yes poster for the Referendum. Mostly, however, the show consists of prints with a literary dimension including several single-page illuminated poems such as Inside the Box of Bone. This is a magnificent challenge to patriarchy, both in the lines of the poem and as patriarchy is personified in a huge, angry, black male figure; neoclassical, even Blake-like in style, a naked female figure is imprisoned within its torso.

We Will All Go Down is another beautiful example of this compound visual and literary form. A reflection on love and mortality, the lines of the poem are inscribed within the curving bank of a stream while a naked woman and a naked man standing in the water are mirrored in blue on its black surface. Beyond them, floating in the water, and also reflected, are what seem to be the heads of two dead men.

Other poems in this one-page format include That Death Will Break This Salt Fresh Cockle Hand, Woundscape and Corruption. The latter includes an image borrowed from Eric Gill of a couple in a close embrace, which Gray also used in his design for the cover of Lanark. Here, however, the lovers seem to be Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden among the animals, then further enclosed in the womb of a huge, sinister female.

In seven plates, The Hippo is an illuminated poem, a translation into Scots by R Crombie Saunders, of a poem by TS Eliot. Now Gray has given Saunders’s translation a visual form. Eliot’s poem is a satire on the church, but Saunders improves on Eliot, and Gray improves on Saunders. The poem opens “The hippo fashed wi’ fleshly thorn,/ Ejaculates in congress grubby. The kirk belcantos/Night and morn./ God is her hubby.” Gray illustrates this with a pair of copulating hippos beneath an image of the female Kirk courting a male God. This group is borrowed from a painting by Ingres of Jupiter courting Juno. Ingres’s Juno is naked and seductive, Gray’s Kirk, however, though also naked, is wearing spectacles, has her hair tied primly in a bun and has rather less erotic promise. In the last verse, as the hippo goes up to heaven, this figure sits smugly while, in Eliot’s words, “the True Church remains below/ Wrapt in the old miasmal mist”, or as Saunders put it, as “the Auld Kirk in the auld mirk,/Foozles below”.

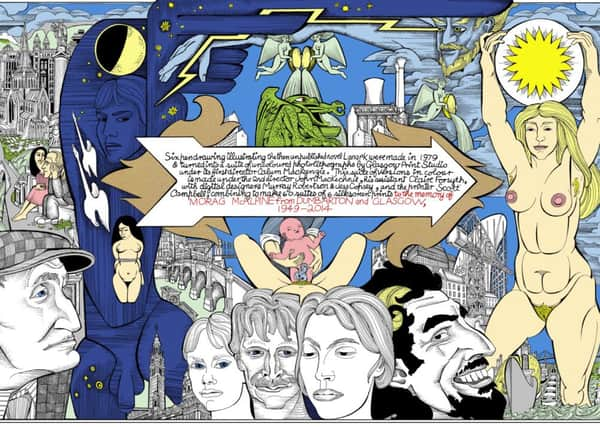

The plates to Lanark are a key part of the exhibition, and in memory of his late wife Morag McAlpine, Gray has produced a new, larger, coloured set of the cover and plates from the original book. There the plates were not illustrations, but a series of title pages. The plate for Book Two is based on an engraving of an anatomy lesson. It is the title page to a 17th-century edition of the Vesalius’s medical classic De Humani Corporis and like such early printed books, Gray’s plates are more an epitome of the text than illustration. Like them too, Gray’s plates are rich, complex and allusive. Masterpieces of intricate design, they incorporate seamlessly an extraordinary range of different scales and perspectives. As a painter, Gray’s real passion has been for large-scale murals – something Blake was also ambitious to do. Indeed, he declared that he wished he could paint pictures in which “the figures are 100ft in height”. Blake never got the chance as Gray has done, but in both artists this ambition reflects, not megalomania, but a driven sense of public mission. Gray has realised this through his novels. You can think of them as vast canvasses crowded with figures, events and fragments of landscapes and this is exactly what the plates to his books are like.

Advertisement

Hide AdIf Glasgow has been Gray’s canvas, for Thomas Joshua Cooper, who came to the city from America more than 30 years ago, it has been the base from which he has travelled far and wide, documenting his travels in his remarkable photographs.

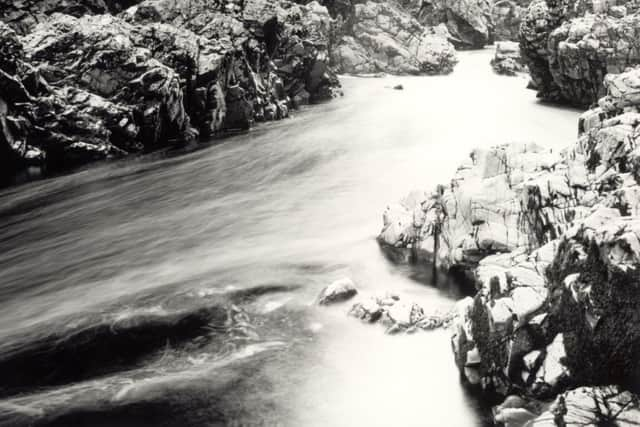

Like an explorer, his photography has been about journeys made, often through very difficult terrain carrying his heavy, antique plate camera and the equipment that goes with it to record a destination which is always some precise point on the surface of the globe. Now, however, a beautiful body of new work is the result of journeys around Scotland to record the rivers that define, not just the nation’s geography, but something much more profound, the poetry that is its lifeblood, almost. Here are pictures of the Findhorn, the North Esk, the Spey, the Kelvin, the Braan and many others.

Advertisement

Hide AdSeven pictures of the Forth and Clyde from source to mouth cross the country from east to west. These are not views, however. They are more intimate than that. Often they are just of rocks and moving water, the gleam of ripples on its shining surface, or in a picture of the Spey at nightfall, little more than the hint of moving water in the dark. As a river flows, it is in constant, restless movement, yet it is also fixed, permanent even, in its course and in the patterns of its flow. Cooper seems to have created a metaphor, in this year of referendum, for something at the very centre of our sense of identity, whether as individuals or a nation: how we reconcile a sense of permanence, a sense of place and a sense of history with our lives as experienced as constantly changing flux. Cooper describes this new work as a love letter to his adopted country – what a beautiful letter to receive.

• Alasdair Gray until 16 November; Thomas Joshua Cooper until 29 November