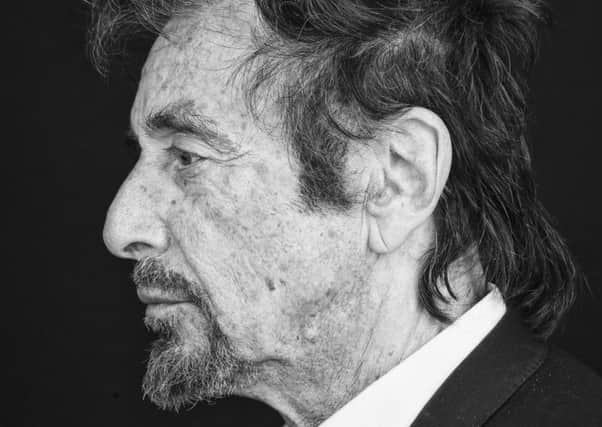

Al Pacino has no regrets about roles not taken

Al Pacino is recalling the time he and an acquaintance were chatting about their lives as they headed to a hospital to visit a friend. “He was basically saying we’re both actors, and I said, ‘You wanted to do it. I had to do it.’”

Acting wasn’t a choice for Pacino, at least not the way he describes it. As a child, he would delight his mother Rose by copying scenes from movies they’d seen. However, growing up in a working-class Italian-American family in the South Bronx, he never imagined that he would one day star in movies himself.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Where I came from, you didn’t become an actor,” he says. “And it wasn’t as accessible as it is now. So being an actor was far removed from our life, from our lifestyle, our thoughts.”

And yet, even before he realised it himself, an actor was what he was. Others saw it, though. Around the age of 12, his school drama teacher, Blanche Rothstein, “took a liking to me,” he says, “and I would read the Bible aloud in assembly – and I did it with a certain verve and gusto – and do plays with her.”

One day, Rothstein climbed the five flights of stairs to his grandparents’ apartment, where Pacino and his mother had lived since his father walked out on them two years after he was born, and as she drank coffee with his grandmother, she said: “Your grandson, he should do this with his life. You have to make him.” Pacino smiles and shrugs. “So I didn’t want to be an actor; I was an actor.”

To be 75 and still working at the rate Pacino is, you need more than just natural talent (honed with years of practice and experience), you need appetite. “It’s taxing and it’s too hard to do this otherwise,” he says. “So far, knock on wood, I’m not there yet. Although I have lost the desire to do many different things.” He gets offered lots of scripts and plays, but “unless I can find something to connect to, I don’t want to take a chance.”

He is talking about a biographical connection, an element of which has always been there in his best work. It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that what he appears connected to most – at least for the moment – is stories about men dealing with the effects of time.

Thus his latest drama, Manglehorn, casts him as a curmudgeonly locksmith in thrall to the memory of a woman he lost years ago, and at odds with his adult son. Pacino gives a subtle, dialled down portrayal of an embittered and prickly man (almost a latterday Scrooge) shuffling towards a kind of enlightenment. David Gordon Green, the film’s director, said the eponymous character is his projection of Pacino; the actor disagrees.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I don’t think he got into my private life,” he says dismissively. “I think he has his own, I won’t call them issues, but he has a torn kind of relationship with his dad and his family. I guess that moves him and he wants to talk about it. I don’t have that.”

As in Manglehorn, age also informed the veteran star’s recent appearances as a wrinkled rock star in Danny Collins, and as a very Pacino-like stage actor, who unlike the man himself is losing his talent along with his memory, in a liberal adaptation of Philip Roth’s The Humbling (released on DVD here as The Last Act).

Advertisement

Hide AdWith his chunky rings, bead bracelet and wild bed-head hair, Pacino doesn’t look like a man who’s going to go quietly into his twilight years. He is still filled with enthusiasm and curiosity for stage and film, which he regards as places to explore the world and himself. He tries not to focus on his age outside of the work, but despite the god-like status accorded him (to his bemusement) by colleagues and fans, Pacino is as mortal as the rest of us.

“I try not to think about [ageing] because you’re not in control. But things happen and the best thing is to just keep going. One morning I get up and I can’t move my neck. The next morning I’m fine. It’s sort of like the drinking days – you learn to take an aspirin before you go to bed when you’ve had a night’s drinking. I recommend it – if you do that.”

Pacino doesn’t “do that” anymore. He has been teetotal (no booze, no drugs) for almost 40 years. Most of the 1970s, during which he made such classics as The Godfather, Serpico and Dog Day Afternoon, are a blur, however. He took his first drink in his teens, and when fame hit him like a tsunami after his appearance as Michael Corleone, he used alcohol as an escape and an anodyne.

Ironically, he hadn’t wanted to do The Godfather because he didn’t know what to make of the character (“I thought, ‘How am I going to play this part?’”), while Paramount didn’t want him because he wasn’t a handsome star like their first choice, Robert Redford. “Nobody wanted me on that movie except for [Francis Ford] Coppola, who I thought was a bit mad.” But the director had seen Pacino’s Tony-winning performance in Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie? and was adamant that he should play Michael. “I must say very lucky me,” says Pacino, laughing. “But I thought he was going to lose his job.”

For someone who strives to disappear inside his characters, the resulting exposure was uncomfortable. He rarely did interviews, partly because he believed that revealing too much about himself would undermine people’s belief in his transformations. Imagine, then, how excruciating it must have been to come out on stage as Arturo Ui and see a line of young women in the front row wearing T-shirts with his face on.

While trying to understand his new life, Pacino turned down opportunities to work with the likes of Ingmar Bergman and Gillo Pontecorvo, because he was young and confused, and felt out of his depth. When Sam Peckinpah invited him to star in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Pacino – who at the time was lying in a hospital bed after being injured in a fall – declined. “It would have been a wonderful thing for me to do, but I told him I didn’t know how to ride a horse. Somehow I used that. But really those were the drinking days, and I thought, ‘With Peckinpah down in Mexico, will I ever come back?’”

Advertisement

Hide AdPacino insists he has no regrets about the roles not taken. “They’re owned by the actors that played them,” he says. “And at the time I was very clear that I didn’t want to do them.” He admits that there are things he wishes he hadn’t done, but doesn’t lose sleep over them. “Regretting is a pointless thing because out of the things you do which you wish you didn’t do, other things come.”

In any case, even if he could remember everything, he hasn’t got time to live in the past. When he isn’t working (he is currently preparing to return to Broadway in David Mamet’s China Dolls), the veteran star is a hands-on father. He has 14-year-old twins, Anton James and Olivia Rose, from his relationship with the actress Beverley D’Angelo, in LA, and an aspiring film-maker daughter, Julie Marie, 23, from a previous partner. He has never married, and has been in a relationship (recent rumours of a split may have been premature) with Lucila Sola, 39 years Pacino’s junior, for almost a decade.

So plenty to keep him feeling young at heart, I suggest.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Yeah, I am young in spirit. Having children sort of supports that because I just love it. And I knew I would.

“I remember when I was a young actor saying I saw myself doing rep somewhere with 12 kids. I didn’t realise what one is, but at the time I was fascinated with that fantasy of having a family.”

Manglehorn is on general release from 7 August