Eddie Barnes: Foes in high places

BEHIND him, dusk was falling on the concrete ramparts of the Scottish Parliament. Huw Edwards, the BBC’s anchor, was up for the day to interview the First Minister, and was pressing him – again – on his plan to keep the pound and whether the rest of the UK would buy into it.

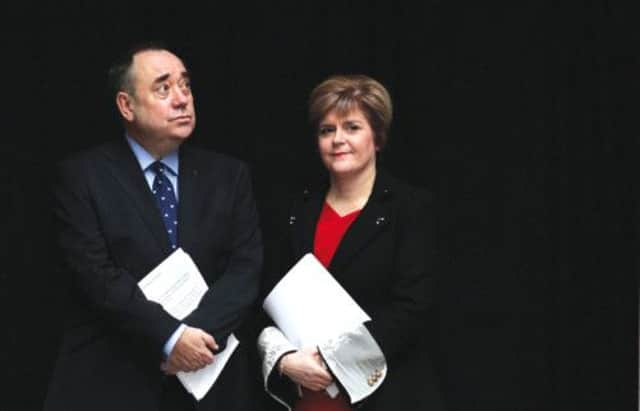

For a moment, Alex Salmond betrayed a flicker of irritation. Complex monetary frameworks weren’t what voters were interested in; what they were interested in were real life issues, he argued. At the launch in Glasgow earlier that day, he and Deputy First Minister Nicola Sturgeon had used the publication of their White Paper to reveal plans for a “childcare revolution”, in which even one-year-olds would get wrap-around care, allowing mothers to go to work in order to boost the Scottish economy. For SNP ministers, the emphasis of presenters like Edwards on issues like EU membership and the currency was all wrong; one declared last week in conversation that these concerns were for the “anoraks”. Salmond’s aides argue that, in conversations with “real” people, things like the currency and the EU don’t come up. What do are bread and butter questions about how independence will impact on jobs and opportunities, and how best to care for their children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd yet, for “anoraks” or not, the UK-wide and international economic implications of Scotland’s choices were what entirely dominated the reaction to Tuesday’s White Paper launch in Glasgow last week – as reflected by the large foreign media presence there. Welsh First Minister Carwyn Jones had already stuck in his own tuppence worth the week before, raising his own problem with the idea of a pan-UK currency pact after independence. He was followed on Wednesday evening when Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy used a press conference to warn that Scotland could not be assured of entry into the EU. Then, on Thursday evening, it was the turn of Sir John Major to insist that a currency pact which would entail Scottish debt being underwritten by English taxpayers could not happen.

The interventions by Major and Rajoy served to overshadow the days following Salmond’s big moment – putting up in lights the glaring fact that Scotland’s independence plans rest on negotiations and the cooperation of outside interests. Yet while the reality of that bigger game became crystal clear, they failed to provide the certainty of outcome for which voters are looking. For the pro-UK side, the missiles lobbed by Jones, Major and Co provide proof that the facts of independence life in the SNP’s document are actually just assertions, and not worth the paper they are printed on. One senior UK politician notes wryly: “Their position seems to be that when they say things, they’re true, but when the Spanish prime minister says things, that’s rubbish.” Hang on, replies the SNP; the truth is that the incoming fire from the rest of the UK and beyond is just political posturing; campaigning tactics which are being engineered by UK spin doctors to scare voters away from choosing Yes (after all, it is noted, Jones only delivered his speech in Scotland as part of a deal with Prime Minister David Cameron and his deputy Nick Clegg earlier this month granting Wales more powers). That scaremongering will disappear like a thawing snowflake once a Yes vote happens next year. So who’s right?

The key issue for debate above all others last week was the currency. The White Paper declared bluntly that Scotland “will” keep the pound. Meanwhile, the well-briefed duo of Salmond and Sturgeon repeated ad nauseam the three reasons why they could be so certain: first, because England would need Scotland’s oil money to help beef up its balance of payments; second, because it would be in the interests of two nations who trade so much with one another; and third, because the pound is already Scotland’s and isn’t London’s to take away.

It sounds simple, but Major insisted in London on Thursday night, it isn’t. Neither he nor anyone in the No camp disputes that Scotland could continue to use the pound if it wanted. The deal-breaker is the idea of a formal currency pact, under which Westminster would have to provide a back-stop for Scotland and its banks (and vice versa) if it was hit by another financial crisis.

“A currency union, which the SNP assume is negotiable, would require the UK to underwrite Scotland’s debts,” declared Major. “That cannot – will not – happen if Scotland leaves the Union. There can be no halfway house: no quasi-independence underpinned by UK institutions.” Pressed on his points on Question Time last week, however, Nicola Sturgeon replied: “That wouldn’t be the case. I would advise Sir John Major to read the [SNP Government-commissioned] Fiscal Commission which set out in some detail how this arrangement would work, including the shared governance arrangements of the Bank of England.” Such issues would indeed be “anoraky” if voters hadn’t, in 2008 and 2009, seen the system go pop in real time, with recollections still fresh of RBS ringing up the Bank of England and the UK Chancellor and warning that the bank machines were about to run dry.

It was because of that that Jones declared last week that Wales would be “uncomfortable” with the thought of “competing governments” adding complexity to such a system. Privately the Welsh leader has said he is puzzled about why Scotland would want to do such a deal anyway given that the UK government would insist as a condition that Holyrood obey tight controls on borrowing and spending. Would Scotland really be independent under such conditions? SNP ministers point to France and Germany, members of a currency union, both of which are independent nations. The Greens’ Patrick Harvie, however, disagreed; real independence will not come if some of the key levers of power are still being grasped by the Bank of England governor and the occupant of 11 Downing Street, he said.

Then there is the EU. With Catalonia’s nascent independence movement at the forefront of his mind, Prime Minister Rajoy put the cat among the pigeons on Wednesday by declaring that he wanted to see the consequences of secession presented “with realism to Scots”. That reality, he claimed, would be Scotland starting life outside the EU. “I respect all the decisions taken by the British, but I know for sure that a region that would separate from a member state of the European Union would remain outside the European Union and that should be known by the Scots and the rest of the European citizens.”

In response, Salmond stuck to his guns, insisting that Scotland would negotiate its membership during the 18-month window between a Yes vote and Scotland’s “independence day”. That would be ample time, the White Paper concluded, to amend EU treaties to add the word “Scotland”, and to negotiate its demands – to keep the UK rebate (to be divided by Scotland and the rUK), and to secure an exemption both from euro membership and from the continent-wide Schengen common travel area. Despite Rajoy’s comments last week, few unionists argue that the Spain would actually go so far as to veto Scotland’s membership. Where they take issue with Salmond is over his assurance that all of Scotland’s terms would be met, and that a painless entry into the EU could be achieved. Spain might give in on entry – but what would it demand in return pour encourager les autres?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo how to weigh these warnings? Is it scaremongering, or just cold reality? On the one hand, it is pretty clear that the nature of the campaign means that the difficulties of independence are being amplified. The UK government is busy coordinating those warning shots on the currency, in the full knowledge that fears Scotland could lose the pound could kill the independence case stone dead. Meanwhile, the very nature of international diplomacy is running against Salmond and Co. In the case of some countries watching on, the orders being given to diplomats in Edinburgh and London is not to do anything that might upset the British giant. Size matters. For others with separatist movements of their own – like Spain – the concern is more down to self-interest. In the case of France, diplomats say self-interest also governs thinking, specifically Paris’s fear that a diminished United Kingdom, perhaps bereft of nuclear weapons, would leave it suddenly exposed. The blunt fact, says Professor William Walker, an international relations expert at St Andrews University, is that the main concern in foreign capitals “is with the rest of the UK – its internal coherence, volatility and future as an international player” – not Scotland.

But that does not mean those concerns are mere empty scaremongering. For example, on Friday, economist Professor John Kay – once hired by Salmond as an economic adviser to the Scottish Government – said the First Minister had “rather stupidly” ruled out a Plan B on the currency. With no axe to grind, he noted that the experience of the Eurozone ensured that the UK Treasury would be extremely leery about forming a new monetary union. “The Scottish Government has stated definitively that it would continue to use sterling in a monetary union,” he added. “There is a slight problem about that, in that you have to negotiate a monetary union – it’s not entirely clear that you could negotiate a monetary union.”

And on the question of Scotland’s relations with the EU, a major conference organised by the Ditchley Foundation earlier this summer attended by foreign diplomats, politicians and Scottish figures concluded that while “there should be no substantive difficulty” in ensuring that Scotland would be signed up, “political” questions over how quickly that happened and on what terms, were numerous. There might be “limited sympathy” for Scotland getting a UK-style budget rebate. The SNP’s preference to keep a border-free UK made sense, but there would also be “pressure” to join the Schengen zone. “The idea of a border check at the Cheviots was therefore not entirely fanciful,” the group declared. And while Spain’s Rajoy was deemed unlikely to actually block Scotland’s entry, “Spanish intransigence could not be ruled out. It was certainly unlikely that Madrid would want to do Scotland any favours,” the group said.

This weekend, that much is obvious. And while it may just be sabre-rattling from Madrid, logic suggests that the same sabre would be rattled ever more vigorously if Scotland did vote Yes. The White Paper is now out there, and offers a target. Helping the unionist case are plenty of friends in high places – Alex Salmond and the pro-independence movement could now do with a few more of their own.

Twitter: @EddieBarnes23