Dr Sureshini Sanders: We need to talk about death and grief

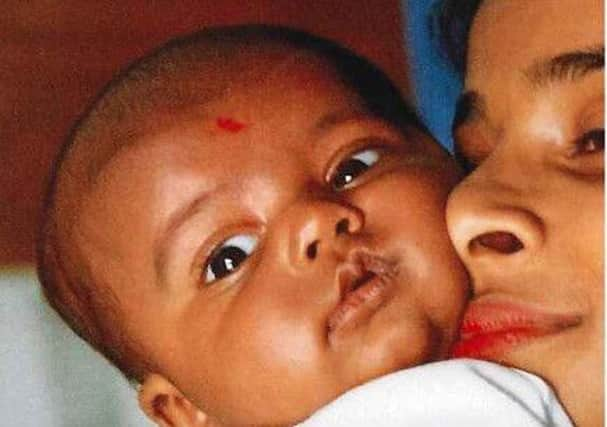

Close your eyes and think of your favourite moment. Was it that first kiss, graduation, your wedding day? For me, it was the birth of a child. The overwhelming love and emotional upheaval took me by surprise. He was born to my sister on a balmy June night in the kingdom of Fife.

Walking about with a bloated abdomen for months and the pain of childbirth may make one appreciate that moment of bliss more, but I could get all the cuddles and playtime, skip the stitches, endless feeding and sleepless nights.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI was appointed as a GP 70 miles from baby. I was young then; finishing work and driving like a maniac for a pre-bedtime play was not a problem. Danny was an easy baby; a quick trip in the car or a dance to John Lennon’s “Beautiful Boy” and he would nod off. Everyone thought he was gorgeous. I was convinced he would be stolen.

The contrast of his dark skin and deep blue eyes was amazing. Sadly, the blue did not last. Once exposed to sunlight, his eyes turned brown. That was mistake number one; we should have never let him out.

When he was two, he stole the show at his nanny’s wedding.

He called me “chinammah”, which literally means “little mother”. “Chinammah, chinammah, look at my toy.” To the horror of the guests, he ran about wielding his sgian dubh which, before our obsession with health and safety, was a real, sharp knife.

We had the perfect relationship, my baby and me. There are no rules for doting aunts. Drum kits, guns, pet frogs, all the thing that parents detest, were acquired. I used to lovingly make my nephew clothes. Hand-knitted jumpers, dungarees in vibrant shades. “There’s a marvellous shop called Mothercare,” my sister hinted.

Then came the birth of my daughter and, as more children came along, Danny accepted a new role, his fair, kind, patient nature made him the perfect leader of the pack.

The tiring and wonderful years of child-rearing, work, friends and caring for elderly relatives passed quickly. Six cousins in all, who would manufacture any excuse to meet, a birthday, a prize at school, a dead pet. We celebrated in the good times, and even harder in the bad times. When my father became terminally ill, each cousin was visited with tummy pains and various plagues which meant time off school with grandpa. Dan started it, and Sam, his little brother, followed.

Danny set the pace for the others, whether by working hard at school, embracing sport, or playing loud music till the early hours.

But before I paint a two-dimensional, perfect picture, I cannot but help listing his faults. It’s only fair.

One, the world does not end at Barnton Junction.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwo, chicken on the bone tastes fine, you should give is a go. I know you emptied the fridge of protein. Don’t deny it.

Three, if you meet a psychopath, cross the street. Mistake number two: we should have encouraged Dan not to try to engage with all those about him. You do not have to stick your hand in the fire to confirm it burns.

Four, it’s fine for me to like possessions. We cannot all be like you, not caring about clothes, cars and decor.

Five, if it is my birthday and I want everyone in ethnic garb for a brief photo shoot, “it’s my party”. Try being cooperative.

While all the other cousins found reasons to escape us, Dan stayed close. In my dreams, he would graduate, live locally, meet a girl (I would never like her; she would not be good enough) and have an army of little Dans.

Now you have seen my happiest hour, let me take you to a darker place, the day my sister called and said, “Dan has had an accident, he is gone.” “What do you mean gone, gone to hospital, gone where?” I shouted.

The Sri Lankan part of me wanted to bang my head and scream but I have been long enough in Britain to hold the scream inside.

“Why us? We have been so blessed. These things happen to other people, not us.”

“Why not us mum?” my wise daughter sighed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere is what I have learned. When you are in hell, as Churchill famously said, “walk fast”. I would add, hold those you love close.

If you can stick to the routine, it will help. Our extended family, wonderful friends and neighbours have carried us.

Make plans, but not too many, enjoy the splendour of the day, take nothing for granted. No one is immune to pain and loss.

It is in darkness that we see the light. Several ministers helped show us the way. Without a certain belief that we will see our boy again, we would have died a thousand deaths.

Mistake number three: to love too much. Remove love and you remove pain. Danny’s funeral was enormous, as he gave his love and companionship to many.

Now, we are in the bereavement club, its membership silent and ever-growing, and are more aware of human frailty and suffering.

I work in end-of-life care, but Danny’s death has taught me more than any textbook could.

My sister tries to focus on the wonderful time we had with him and that we were blessed. I say 23 years is not enough; we have been robbed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe has returned to full-time work as an eye surgeon, finding solace in service to others. Maybe, as many Hindus have told me, he was too good for this world.

His stone will read, “Glorious youth, loved by many, kind to all.”

Danny showed us how to love life, and give of our best.

After the support we have had, I realise that Dan was right; the world does end at Barnton Junction.

Dr Sureshini Sanders is an NHS community geriatrician in West Lothian.