How Scotland celebrated the Queen’s coronation

In a resolutely non-Royalist household in the West End of Glasgow, something was stirring.

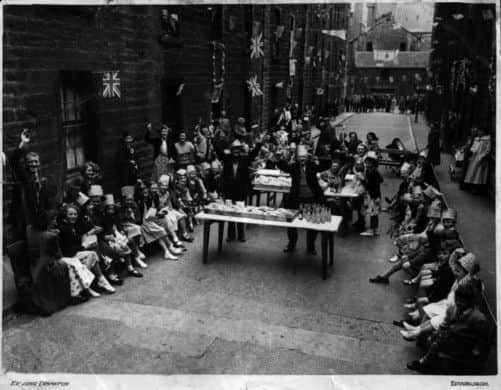

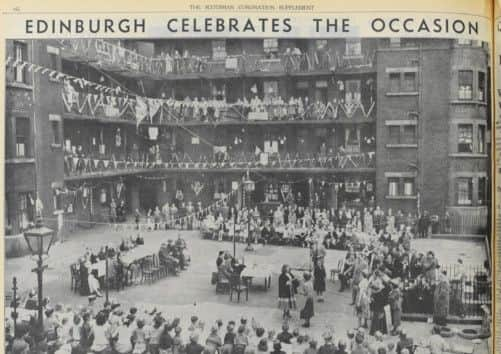

Christina Morrison recalls: “My mother found a Union Jack on a pole and stuck it out the kitchen window. That was extraordinary for us. We never usually bothered about things like that.” The Morrisons were not the only family to come over all red, white and blue for the coronation of Elizabeth II. Across Scotland, from the streets of the capital to the remotest villages, there were bonfires, concerts, parades and street parties. Trees were planted, children dressed in DIY ermine robes, factories adorned with twinkling lights. Thanks to the newfangled miracle of television, families and neighbours jammed into living rooms to watch the young monarch take the throne.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn their first-floor flat in Havelock Street, the Morrisons had taken delivery of their first TV. “It was a tiny little Bakelite thing,” Morrison says “a gift to my father from the staff at the school.” The extended family – including the youngest, still in her pram – gathered to watch the events in Westminster Abbey unfold.

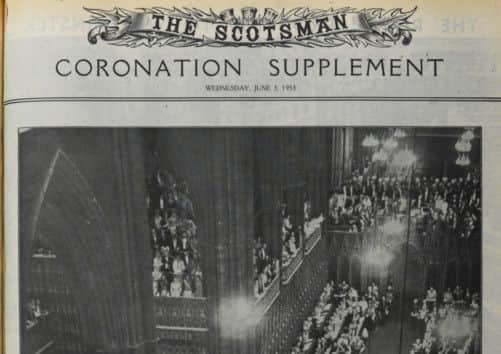

“It was marvellous to see it,” says Morrison, who, at 85, is two years younger than the monarch. “It was most spectacular. There was wonderful music and we were all terribly impressed by the telly although it was wee by today’s standards. We were all crowded around it. In fact, my abiding memory of that day is crowds. That poor girl with her orb and her sceptre, and all these men in long goonies crowding round her. She had no space at all.”

The previous generation had experienced a coronation – of Elizabeth’s father, George VI – on the radio. Morrison and her contemporaries were the first ones to watch a national event in real time, in the comfort of their own homes, accompanied by the reverential commentary of a member of the Dimbleby family. (Richard Dimbleby, father of Jonathan and David, was on duty that day.) It was the start of appointment television as we know it.

A Scotsman correspondent noted: “As we kept our eyes on the little screen, perched on a raised stool, we had to remind ourselves from time to time that we were not in the Abbey itself. Those who, at the beginning, were mistrustful of televising the Coronation must, by now, be completely converted. The true meaning of the Coronation has been brought home to, literally, millions of people. We felt a tremendous debt to Mr Dimbleby and the engineers for the superlative performance which they staged. It reached the high diginity and solemnity of the occasion itself.”

The TV retailers of the nation, charged with delivering the longed-for images of the golden carriage, the crowds lining the Mall and the family waving from the balcony, took their responsibilities very seriously. The Scotsman reported one Edinburgh dealer who had 14 engineers on standby, with four vans waiting to repair TV sets all across the capital. They made 50 calls on 2 June.

In Wick, where reception was unreliable in the extreme, shopkeeper Frank Gunn erected special Belling & Lee aerials and masthead amplifiers so that no resident of Sutherland should miss a moment. It worked. Gordon Johnson, from Caithness, who was ten at the time, recalls “spending most of Coronation Day in a neighbour’s house with my family, watching the TV transmissions from Westminster Abbey. I recall them as grainy black-and-white pictures but, not having a TV at home, the experience was wonderful. Seeing my first television pictures made more an impression than the Coronation itself.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The Queen being so young was another point that made an impact. Most adults seemed old to me, except for her.”

The Big Society was out in force that June. Those who didn’t have a set of their own piled round to watch with friends and neighbours, or to schools, clubs and hotels. The Monsigneur News Theatre in Princes Street, Edinburgh, brought in two TV sets and 350 people watched the big day together there. Even prisoners had the opportunity to see the new monarch swear her oaths. After much debate it was agreed that the residents of HMP Barlinnie would be allowed to watch the Coronation in “shifts” of around 50 at a time. This would, the governors optimistically suggested, awaken their latent “civic consciousness”.

Advertisement

Hide AdMany of the day’s picnics, parades and concerts were organised by schools, churches and scout troops. In Leven, despite stringent security, vandals sneaked past the scout guard and lit the bonfire before the big day. There had been no such incident on Arthur’s Seat, where a magnificent blaze could be seen from across the city. Lads from Thurso built and lit bonfires on Ben Morven, Warth Hill and Olrig Hill despite high winds, snow, sleet, fog and lightning in the run-up to 2 June.

Civic leaders, chains of office jangling, were out in force. In Lossiemouth, the serving provost, the previous provost, the Laird of Pitgavney and various military dignitaries braved the breezes of the Moray Firth to plant trees in honour of the occasion. Schoolchildren were marched across a field and assembled around the site. The provost made a lengthy speech. His wife, resplendent in fur coat, hair still warm from the dryer, picked up a shovel and got the earth moving.

In Glasgow, the night before the Coronation there was a party to rival Hogmanay. George Square was lit up; there was a Royal coat of arms on the wall of Glasgow School of Art (praised by The Scotsman as “a gay and imaginative display”); the lord provost toured the city to admire the decorations and personally thank the folk responsible. In Edinburgh, the floral clock in Princes Street Gardens was the epitome of pansy-based patriotism. The capital’s shops experienced a last-minute rush for baked goods, other provisions, flags and Coronation decorations.

Some Scots had more to do than wave a flag or overdo it on the iced buns. Dennis Whitehead, a 13-year-old chorister from Hawick, was one of 20 boys chosen from churches around the country to sing at the Coronation service. He spent the month before 2 June at Addington Palace, a stately home in Croydon, practising under distinguished choirmaster Edred Wright.

On the day itself, he had to be robed and ready by 6.30am before going to his seat. He recalls his lunch: “Ovaltine tablets, glucose tablets, barley sugar, bread and butter, an apple, a quarter pound slab of chocolate, all of which was consumed before the service began.”

He kept a detailed diary of his experiences. On 2 June, he wrote: “I must confess I could not sing the first few notes because of a lump in my throat. I shall never forget as long as I live the thrill of that moment … the picture will remain for ever in my memory.”

Advertisement

Hide AdBack at home in the Borders, his parents watched the service on a black-and-white television but didn’t catch a glimpse of their son.

Then it was all over. The bunting was taken down, the trestle tables and tea urns returned to church halls. Life returned to normal. Only the souvenirs – mugs, model carriages, crown-shaped money boxes, red and blue propelling pencils – remained. (In some ardently monarchist households, they remain in the piece of furniture known as “the good unit” to this day.) And the memories… “I remember my husband closed the surgery,” says Chrstine Morrison. “He was a dentist with a new practice. He never closed the surgery. But he did for the Coronation.”