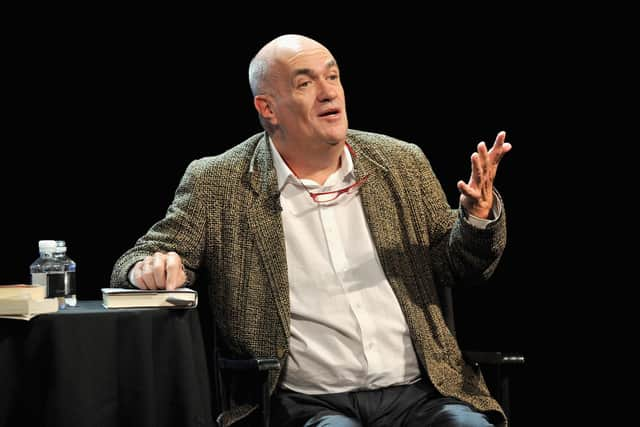

Book review: A Guest at the Feast, by Colm Tóibín

Novelists used quite often to publish a collection of essays from time to time. It kept them in the public eye in a fallow period, and further back in the 19th century might establish them as serious writers. This was the case with Stevenson, for instance. Most such essays had usually appeared in magazines. Things are different now. The market for the long essay has dried up. Two or even three thousand words, fine; anything more than that – well, you have to be fashionable as well as good to find an outlet. Happily, Colm Tóibín is both. Most of the pieces in this collection were published first in the London Review of Books, spread over more than one issue; one in The New Yorker, one in the Dublin Review.

The first essay – “Cancer: My Part in its Downfall” – is the most personal. Indeed, except for other essays which recall childhood in Wexford and in Catholic schools, it is the only one which draws directly on his own emotional life. Yet, not surprisingly, the central themes of the collection are the crumbling of Catholic Ireland and the Catholic Church’s worldwide loss of authority. Tóibín grew up in an Ireland at a time when any expression of his sexuality was not only deemed immoral but criminal.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere are essays on the present Pope and the two before him; Benedict XIV and John Paul II. All are intelligent, sometimes disturbing, often surprising to non-Catholics. He views Pope Francis with a cold eye, deploring, with good reason, his silence as a young bishop in the dreadful years of the Argentinian Junta when tens of thousands were made to “disappear” and vile torture was routinely inflicted on “enemies of the State. The “Polish” Pope was “paradoxical”; for him, “the events of Polish history are viewed as part of a struggle between God and Satan”. This is understandable in view of Poland’s history, and yet, in the great crime of the 20th century – the Nazi holocaust, the attempted extirpation of European Jewry – Polish hands were stained. Tóibín is sympathetic to Benedict despite his hardline views on homosexuality, birth control and abortion. This is, one might think, no more than to say that in these matters Benedict thought as most Christians and almost all Christian Churches did until the last quarter of the 20th century.

Tóibín may have lapsed but he remains fascinated by religion, never able – or perhaps willing – to escape the consequences of his Catholic childhood and education. There is a very interesting essay on the American novelist Marilynne Robinson, not only a practising Christian but also a Protestant well read in Protestant theology and an admirer, indeed a student of Calvin, something rare in literary circles – a very good novelist and essayist, as Tóibín recognizes. Orwell, in one of his stupider moments, wrote that the novel is a Protestant art form, and though there have been many good novelists who were also devout and only sometimes questioning members of the Roman Church, Protestant ones have a freedom denied to their Catholic colleagues. They are freer to question and they don’t have to believe that the bread and wine in the Communion service are translated into the body and blood of Christ. This is an essay in which Tóibín engages compellingly with questions of faith.

There were many in the last century who swithered between Catholicism and Communism. The two faiths had this in common: they demanded much of faithful believers and their absolute authority led to corruption of the spirit and the intellect. Toibin is fierce in his denunciation of the sexual abuse so long practised with impunity by the Catholic Church. Yet he recognizes that he was formed by his Catholic family and education, and looks back with a mixture of gratitude and resentment, regret and indignation.

There is nothing flashy about these essays, no showing off. They are always interesting and intelligent, written in an admirably clear prose free of academic jargon. In short, this is journalism at its best. I learned a lot from them and am grateful for that. It’s a collection to which I will surely return, just as I do to Orwell’s, Ian Jack’s, Ferdinand Mount’s and Patrick Marnham’s.

A Guest at the Feast, by Colm Tóibín, Viking, 299pp, £16.99