Art reviews: Gary Fabian Miller | Impressions: Two Centuries of Printmaking

Winter Blaze, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh *****

Impressions: Two Centuries of Printmaking, Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Photography was a chemical invention, not a breakthrough in optics. The principle of the camera had been known for centuries. The new magic was the chemistry of film, paper and process. Though the optics grew ever more sophisticated, that remained true. For most of two centuries photography was an analogue business. Through all the various stages, there remained a direct relationship to the original thing seen, an analogy in fact, but with digital, a string of ones and zeros, no analogy is possible. This completely new form of photography has meant the demise of the analogue industry and all its chemical magic. A whole economy has vanished.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGarry Fabian Miller is one of a number of artists for whom this demise is existential. He uses a light sensitive photographic paper called Cibachrome, but in 2012, the company behind it ceased production. In the face of digital, it was no longer economic. He bought what he could but is now at the end of his supply. This is why his exhibition at the Ingleby Gallery is called Winter Blaze. It follows an earlier exhibition and book called Blaze. Not just a blaze of colour, though it is certainly that, it is an envoi. If he has to stop working in the remarkable way that he has done for several decades, he is going to go out in a blaze of glory. As I saw his show in the Ingleby Gallery with sun coming into the big white space through the skylight and two oculi, circular windows, high up in the south wall, the images seemed to pick up the patterns of light and distil them into colour. The whole thing was just that, a blaze of glory. Beneath those two oculus windows, four works Midwinter Blaze I, II, III and IV, have the title of the show. Across the four images, like phases of the moon against the black of a night sky, a crescent of blue-white broadens across a shadowed circle of deep blue. Matching the circles of sunlight in the oculi above with the sliver light of the moon, it is celestial.

Fabian Miller is a photographer, but he doesn’t use a camera, not even a pinhole, the elementary form of image projection that artists used long before the invention of photography (“Camera” is Italian for “room” as in camera obscura, a dark room). Cibachrome, Fabian Miller’s medium, is a dye-destruct colour printing paper. Developed in the 1940s, it is so called because the colours are actually dyes in the emulsion. Revealed by bleaching out, they are not the product of chemical changes. This means the colour is itself, not an evanescent process. It has unique richness, sharpness of image and also permanence. Fabian Miller’s method is to expose the Cibachrome to carefully arranged coloured light transmitted through liquid or some other medium. Nothing intervenes. Exposures are slow and the image is unique. It is a bit like daguerreotype and some of the earliest forms of photography where the final image is also direct without any intermediary stage. Here the effect is stunning. It is as though colour has been triple-distilled to its purest form.

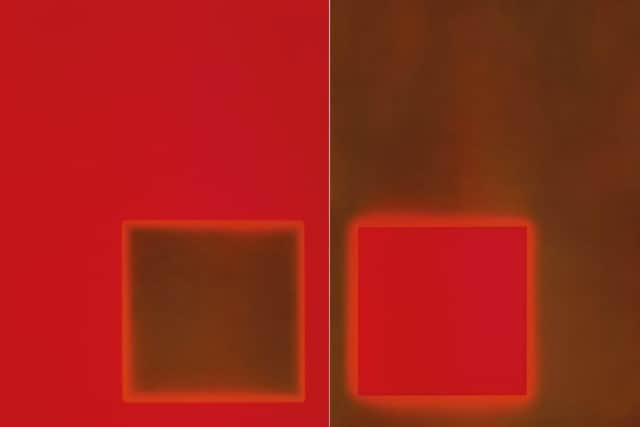

Fabian Miller’s iconography is mostly that of abstract art. There are memories of Josef Albers, for instance, in There is No Shadow, but it is no more than a memory, acknowledgment of an appropriate pedigree, perhaps. The imagery is his own. He lives on Dartmoor and is very aware of the natural world around him and while his work is certainly abstract, you feel nature is not far away. There is No Shadow, for instance, is a disk of purest yellow set against a warm white field. The outer edge of the disk is sharp, the inner edge slightly feathered. The effect is a ring of pure sunlight hanging in space. The three works of a series called The Cairns show a different side. The title reflects the conical shape of the images, but, rather than the stones of a cairn, the piled-up layers seem almost liquid as though the light from a candle was catching water flowing over stones. No mere chemistry, this is alchemy, and it is both mysterious and beautiful.

Another work, A Lost Colour World, one of the most striking things here, is perhaps in its title an epitaph for Cibachrome. It is composed of four large coloured disks overlapping against black. The two disks at either end are red but, cut off by the frame, are only semicircles. Between them are the full circles of a blue and a green disk. At the point where the disks overlap the colour changes, but not in the way you would expect. Red and green produce orange. Green and blue produce light blue, and red and blue, pink. The effect is space, light and movement, music almost.

This work is nearly three metres across, however, and is on a single sheet of material without joins. Cibachrome was never that size. Faced with the end of his supply, Fabian Miller discovered a miracle paper for digital printing called Lambda and since then he has worked in partnership with John Bodkin, an expert in digital printing. The works in this show are digitally printed from scanned Cibachromes. While for now it is still dependent on his nearly exhausted supply of Cibachrome, this new process has nevertheless opened up new possibilities, not least of scale. That works superbly here – these beautiful images command this lovely space.

Technically I suppose Fabian Miller’s works are now prints, though except in scale they still have all the qualities of his Cibachrome originals. There is no shame in printmaking, however. It is a distinguished tradition and a show at the Open Eye, Impressions: Two Centuries of Printmaking, brings together some familiar and some less familiar masters and mistresses of the art. Two intricately beautiful etchings here, Wild Bees and Butterflies by Katherine Cameron, show she could hold her own with her brother, DY Cameron, who is also represented by several fine prints.

Gerald Leslie Brockhurst was also an accomplished printmaker, but while he is well-known, ES Lumsden and Hedley Fitton are somewhat less familiar, though both produced superb prints. Mary Viola Paterson’s nicely observed lithograph of people promenading on the Champs Elysée reveals an amusing but unfamiliar talent. Among more recent artists, Sandra Blow’s abstract Double Diamond is a match for two bold prints by Alan Davie. Peter Howson’s huge and striking woodcut, The Heroic Dosser, from 1987 is as good as anything he has produced. As well as all these you can choose from screen prints by Paolozzi, Cubist landscapes by Paul Nash, or etchings by Wilkie and James Kay. Altogether it is a nice anthology. Duncan Macmillan

Gary Fabian Miller until 20 December; Impressions until 28 October