Full story of the iconic Iona cross revealed

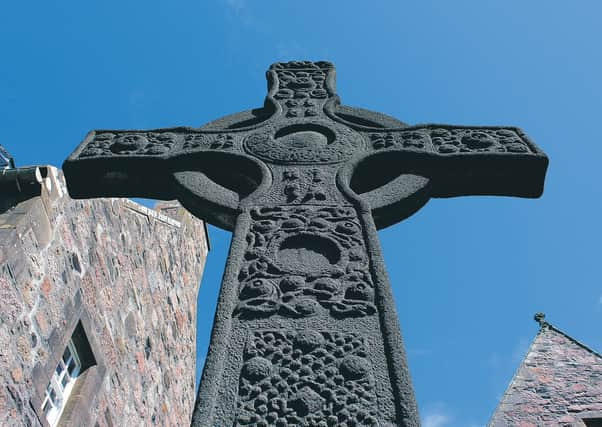

Few visitors to the tiny island of Iona, in the Inner Hebrides off Scotland’s west coast, leave without taking a picture of its famous abbey and the magnificent cross standing outside.

Every year the island attracts pilgrims and tourists keen to follow in the footsteps of Saint Columba, who arrived from Ireland in 563AD to spread the Gospel to Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut unlike most of the other artefacts on Iona, the story of St John’s Cross, which stands proudly in front of the saint’s shrine, has never properly been told – until now.

The reason? It is a concrete replica of the 8th-century original, arriving on Iona in 1970 sitting incongruously on a boat delivering the island’s annual supply of coal.

In March, the concrete cross was given a category A listing by Historic Environment Scotland (HES), reserved for “outstanding examples of a particular period”.

Almost exactly 50 years after it was erected on 6 June 1970, a new book has told the story of the replica and argues that it must now be treated as a monument in its own right.

The book, by University of Stirling academics Dr Sally Foster and Professor Sian Jones, also raises the question of whether other replicas around the UK have acquired their own unique historic significance.

“The St John’s cross is on all of the tea towels, the magnets, all the postcards and souvenirs – it’s iconic,” Foster says. “But it’s also little understood, and from a formal heritage perspective, under-appreciated.”

The designers of the replica cross knew it had to resemble the original in colour, texture and detail and be durable enough to withstand Iona’s often extreme weather.

As well as being cast in concrete, it was reinforced with 5mm nickel steel bars to resist strong winds and the corrosive effect of sea spray. Colour samples were even taken from where the original cross – which is thought to have collapsed soon after being constructed and now lies in the Abbey Museum – had been quarried. A black iron oxide pigment was also used to give an ageing effect.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJustifying its category A listing, HES cited the “scholarly, artistic, engineering and craft skills” that went into its construction, adding that it had since become “an integral part of the history and contemporary experience of Iona”.

“For me, listing a replica was really interesting philosophically. It shows how something created not that long ago has quickly become part of our cultural life,” said Elizabeth McCrone, head of designations at HES. “It’s a cultural and philosophical mind shift to not think of a replica as having less value than the real article. We need to evolve the way we look at our heritage – as history never stops.”

Foster first became interested in replicas when she realised they were not being researched or valued, which she ascribes to people’s “slightly snobbish” views. “These things were still being destroyed or put in skips [by museums], as there was no understanding of their significance,” she says.

The research she did with Prof Jones is to form the basis of guidance for museums and heritage professionals, encouraging them to think more carefully about the value of their replicas.

Another remarkable story concerns the Hilton of Cadboll stone, an intricately carved Pictish cross-slab dating back to around 800AD, which once stood at a medieval chapel site adjacent to the village of Hilton in Easter Ross.

The original was removed from the village in the 1860s by the landowner and is now on display in the National Museum of Scotland. When a local campaign to return it to the village failed, it was decided that a replica should be commissioned in its place.

The full-scale replica was hand carved by sculptor Barry Grove and was erected in 2000 at the medieval chapel site in Hilton.

But the project also led to a fresh excavation, which turned up a missing piece of the original.

Prof Jones, who has studied the episode extensively, says people in the village talked about the original stone “almost like it was a member of the community”.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.