Who can resist a Guinness?

Is there anything worse than a convert? Such enthusiasm, such zeal, such a high tolerance for trivia. Unfortunately, the convert I’m referring to is me.

My conclusion is unavoidable since the other night in the pub I witnessed myself leading a demonstration as to how to drink a pint of Guinness. “Elbows up,” I commanded. “Eyes to the horizon....” There were several other people at the table drinking pints of the black stuff, and without casting aspersions I’m going to hazard a guess they had indulged in that activity quite a bit more than me, and yet I took it upon myself to lead what I humbly described as a masterclass. “Don’t sip the head as you would with a lager – it’s too bitter. Suck the liquid through the head and what you’ll taste is sweetness. Do you taste it? Do you?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdObviously there is no excuse for this kind of pub bore behaviour. There is, however, an explanation.

I blame Fergal Murray. Murray is the master brewer of Guinness, a man who has spent more than 30 years combining water, barley (malted and roasted), hops and yeast to make millions of pints of Ireland’s most famous export. He has also poured pints for the Queen (“she drank it with her eyes”), and a month or so ago, Tom Cruise (he quaffed his and apparently his chat was “very genuine”) and as a story teller he is a man who has kissed the blarney stone. “We started our careers at the same time,” says Murray of Cruise. “I was 19 when I started brewing and he was 19 when he starred in Risky Business. I did say to him ‘you’ve done well, Tom.’”

When Murray is standing behind a bar with the intention of teaching you how to pour a pint, you do tend to concentrate. “You place your four fingers down the glass in a row from the harp,” he says, before digressing into a long story about his favourite bar in Jamaica, an establishment called Luckies, where bottles of Foreign Export Guinness (a stronger brew, 7.5 per cent no less) sell by the truckload since it’s a drink that perfectly complements a hot and sultry evening of dancing. Apparently. Back to the fingers. “You hold the glass at a 45 degree angle to the tap, you pull the handle forward until it’s horizontal and fill the glass up the top of the harp, straightening it as you pour.” At this point you stop, and if you’re Murray and never want to miss a branding opportunity, you put the glass on the bar rotated so the salivating punter can gaze at the liquid which is by now doing that amazing cascade effect before their pint is finished. He picks up the glass again. “Now you top it up by pushing the tap handle backwards until the head is just proud of the glass.” Murray doesn’t bother with shamrock doodles or anything else, he’s happy with his pint just as it is. It is a form of perfection reached in precisely 119.5 seconds.

And I confess, it looks delicious. It’s the surge that gets you, all that lovely cascading as the liquid settles. I could, of course, bore you with details of how velocity and friction combine with molecules of nitrogen and carbon dioxide to create that unique effect but let me just say this: it’s really pretty.

Unless you’re planning a career as a bar tender, knowing how to pour a perfect pint of Guinness might seem like redundant information, a bit like say, knowing how to chop off a champagne cork with a sabre (I can do that too, but that’s a lesson for another day), but here’s the thing, you’ve now got a way to entertain yourself when you’re waiting at a bar, trying to catch some frantically busy person with the allure of your crumpled fiver: you can assess their Guinness-pouring technique. I’ve been doing it for the past couple of weeks and you’d be amazed at how many variations there are. But the basic rules are the ones Murray has laid down as he stands behind the Conniesseur’s Bar in the historic Guinness Storehouse in the centre of Dublin.

Guinness is as much a part of the fabric of Dublin as the River Liffey. It’s not just that the St James’s Gate Brewery site, first leased by Arthur Guinness in 1759 when it was just four acres, now occupies more than 50 acres, a huge chunk of the city. Guinness has played an indelible part in the city’s industrial, social and cultural history – from the philanthropy of the Guinness family in the 19th century that saw slum clearances and the building of swathes of better quality housing for city dwellers, to the fact that by 1930 one in 30 Dubliners were reliant on the Guinness brewery for their livelihood. When Arthur Guinness paid £100 down payment and signed his 9,000 year lease he marked the beginning of a relationship which still shapes Dublin, despite the fact that the seven generation tenure of the Guinness family ended in 1992 when Diageo bought the brewery. Incidentally, Guinness was not a wealthy man when he took over the site. He’d been left a hundred quid from his godfather a couple of years earlier and that’s what allowed him to come up to Dublin from County Kildare, where he was born, to make his fortune. The signature on the famous lease is the one that still appears on every can or bottle of the drink.

When Arthur Guinness started out, in the mid-18th century, the beverage of choice was ale rather than stout. It wasn’t until the 1720s that a dark beer, known as porter, was invented in London. The name came from the punters who drank it – the porters who worked in Covent Garden and around Billingsgate market. Porter was imported into Dublin but it didn’t take long before brewers in the city decided to try to make their own. So Arthur Guinness didn’t invent the drink that made him famous, and his family very wealthy, he took an existing recipe and made it his own.

“When you brew Guinness,” says Murray, “the four distinctive elements are: roasted barley – we’re the only brewing company in the world that has its own roasting facilities – which gives the ruby red colour and the caramel and dark chocolate notes; extra hops, double the amount you’d find in an average lager; the way the yeast used in Guinness operates, which means you end up with a fresher beer.” And finally, the magic ingredient, what Murray calls a “special brew”, which is added as the beer matures. “It’s like seasoning,” he says. “It brings out all the flavour.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

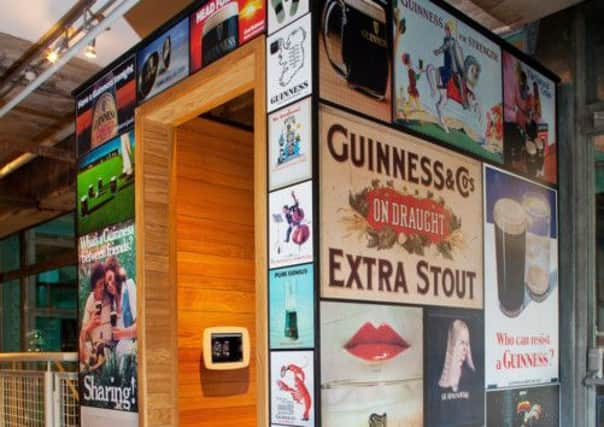

Hide AdThe Guinness Storehouse was the brewery’s fermentation plant from 1904 to 1988. Reputedly the first steel framed building in the British Isles to be built in the Chicago style, the steel for the construction was provided by Sir William Arrol and Company who also provided steel for the Forth Bridge. In the 1950s it was converted into a sterile plant, the wooden tuns replaced by aluminium ones, but by the 1980s the building was becoming obsolete. It was relaunched in 2000 as a giant and now hugely popular tourist attraction with a central atrium in the shape of a Guinness pint glass. Criss-crossed with escalators and dotted with memorabilia and artifacts from the brand’s history, it looks like it could be a sort of high concept department store or advertising agency, apart from the fact that lots of people are walking around with pints of Guinness in their hands. “We don’t really encourage that,” says Eibhlin Roche, the company’s archivist, a woman with a truly encyclopaedic knowledge of all things Guinness, as she guides me towards her department, replete with antique bar taps and a large model of the Guinness Toucan designed by John Gilroy back in the 1930s. But clearly it’s not easy to be too stern with thousands of international visitors (including, intriguingly and somewhat inexplicably, a disproportionately high number of Italians) who’ve travelled here to pay homage to the tipple and who partake as they wander through the exhibitions.

“The first newspaper ad ran in February 1929,” says Roche, handing me a copy wrapped in plastic. It contains the famous slogan ‘Guinness is good for you’, although that’s not a claim that in these health-conscious days anyone would be willing to stand by.

“By the mid-1930s, artist John Gilroy had created his toucan, ‘Tookie’” Roche says. “That became one of the longest running advertising images, surviving for nearly 80 years. In fact, he first drew a sealion, then it was an ostrich and then the toucan. He even created a zookeeper, modelled on himself, to keep charge of the menagerie he’d created.”

One benefit of being on the same site for more than 250 years is that there’s a wealth of archive material recording the history of the brewery. There’s the printer’s proof of the first label using the harp, dating from 1862. Based on the 14th century ‘Brian Boru’ harp still preserved in Trinity College, the company registered it as a trademark in 1876, which was a little awkward when the Irish Free State Government came into being in the early 1920s and decided that they too wanted to use the harp as the symbol of Ireland. They got round any legal problems by flipping it the other way round.

Roche passes me a brown glass bottle embossed with a map of the world. “In 1959,” she says, “when Guinness was celebrating its 200th birthday, 150,000 of these bottles were dropped into the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans.” Inside the bottle there was a scroll, purportedly from King Neptune informing you that you’d found a Guinness bottle and asking you to send the geographic coordinates where you’d found it to Guinness’s export office in Liverpool. “About every year to 15 months a letter will wing its way here to us in the archives from someone who tells us that they’ve just found one. The last one was found a year ago, near Sydney, Australia. The one before that was picked up in Greenland.”

There’s no doubting, then, the global reach of Guinness, but Murray contends that ‘Guinness adorers’ as he calls them, are the drinkers who know the best pubs. So, what are his recommendations? “I can’t really recommend specific places,” he says, “because the bars I don’t mention will be upset.” Oh come on, I persist. He says he’ll tell me where he’s had “good experiences” recently instead.

“D4 in Wellington, New Zealand,” he says. “A lovely bar set up by a guy who loves Guinness. That’s a great place. And last week, I was in the first Irish bar in Jakarta, of course called Molly Malone’s. Draught is not pervasive in Indonesia, but the guy who’s set that up thinks he can do it. Lovely. In February I was in downtown Cincinnati, in a place called Arthur’s. It’s been there since 18-whatever, a proper old-world bar. It was late, it was snowing outside. We’d been doing a big gig and we just needed a pint. Beautiful, a great spot.” His final recommendation is a bar called Ulysses in New York. It’s close to the Stock Exchange building, where Murray has rung the bell on St Patrick’s Day on many occasions. “It’s a great place. Tom Cruise knows it too,” he says, as he tips his glass at 45 degrees.